Product Backlog Refinement—TL;DR

Where to start when kicking-off an agile transition?

Usually, tools and processes are smallest the common denominator among all participants, as they are at the core of the grand scheme of agile things.

It is a rare occasion that you start from scratch with a brand-new team without an existing product, probably even in a more or less nascent organization, for example a startup.

In most cases, an existing product delivery organization with available products, and services will go “agile“. In this case, turning attention to the available product backlog is a pragmatic first step. The following process describes what aspects need to be attended to to optimize the outcome.

Refinement of the Existing Product Backlog

Starting the agile transition with an extended product backlog refinement session has also proven to be an effective way of coaching a new team. Ceremonies, practices, and artefacts, as well as agile principles can be introduced “on the job”, so to speak, using break-out session whenever required.

Such an initial refinement workshop may require—depending on the maturity and size of the organization and its products—several hours or even several sessions.

As far as the kick-off in general is concerned, the product backlog per se is an interesting artefact as it provides a deep dive into the product delivery organization’s history. Almost like an archeologist digging through layers of an ancient civilization, you can identify organizational debt, process insufficiencies, problematic product decisions, and other anti patterns by sifting through the backlog.

Product Backlog Anti Patterns

Typical anti patterns that can be found in legacy product backlogs are, for example:

- The product backlog is structured is a waterfall manner:

- There are no team projects…

- …but solely projects spanning the whole organization or division to ease the reporting process. (The “70% finished” syndrome.)

- The product backlog is a long, unstructured list of ideas, features, bugs, minor technical tasks, change requests, and epics—and thus practically not in a state anyone could effectively work with

- The prospective value of tasks is not reflected by a ranking, as prioritization is due to the sheer size of the product backlog no longer an option

- There is no consistent quality in building user stories, e.g. based on Bill Wake’s INVEST principle

- There is no “Definition of Ready” applied to user stories

- A significant proportion of user stories consist of barely more than a headline without any additional information on the “why” or “how”

- User stories are being kept in the product backlog for months without being improved over time, accomplished, or archive for lack of value

- Product backlog items are being created directly by everyone, e.g. stakeholders, and not just the product manager or Product owner

- Product managers already create (sub-)tasks and assigned them directly to developers.

How to Apply Structure to the Product Backlog

How to get from potentially hundreds of unstructured “user stories” hidden in the legacy product backlog to a valuable product backlog in an agile sense?

To my experience, there is only a single way to achieve this: Inspect each item in the legacy backlog and decide collaboratively with the whole team whether the issues is worth working on or not.

A process for this procedure may look like the following:

- Step 1: Identify all relevant tasks for the newly created team—probably distributed across several projects—, and migrate those deemed valuable to the team’s new project.

- Step 2: Kick-off the refinement process with creating shared understanding on:

-

- The purpose of the team’s product backlog in general

- That the product backlog isn’t supposed to be a bucket for each and every idea

- That a valuable product backlog covers rarely more than a period of maybe 6-8 weeks.

-

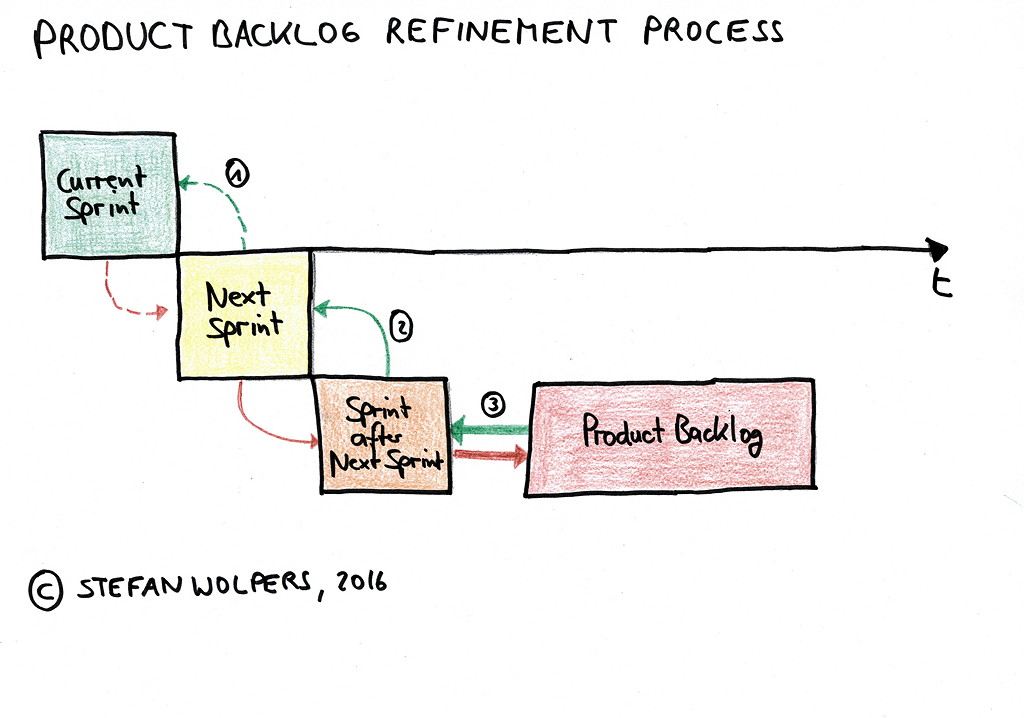

- Step 3: Introduce the product backlog refinement process, why it is beneficial to divide the original Scrum sprint planning ceremony and create a separate backlog refinement ceremony:

- To defuse the sprint planning meeting in the first place. (Who wants to spend eight hours on that?)

- To be more flexible responding to change while working on user stories

- To provide the Product owner with better options to answer questions of the Scrum team in a timely manner. (It’s easier to do that once or twice a week than every 2 weeks, for example.)

- To create a smooth process including the graphic and UX designers. (Creating deliverables collaboratively becomes thus much simpler.)

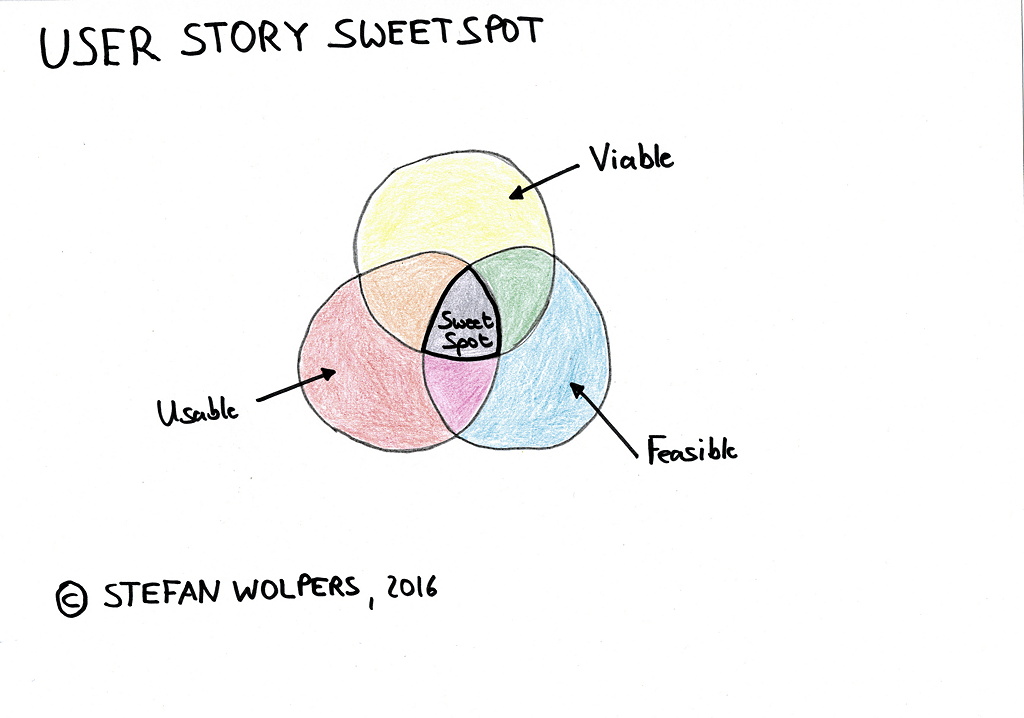

- Step 4: Introduce the Scrum team and the Product owner to user story best practice, for example Bill Wake’s INVEST principle. Visualize the sweet spot of value, usability, and feasibility. The team needs to embrace the idea that a user story is primarily a token for discussion.

- Step 5: Create with the Scrum team and the Product owner their version of a “Definition of Ready”

- Step 6: Kick-off the estimation process by introducing the “Estimates are nothing, estimating is everything” idea:

- That estimating is all about knowledge transfer, and creating a shared understanding of the “why” a user story is valuable, and the “how“ it might be realized

- That estimates are a metric for the Scrum team

- That estimates are defined in relative sizes—t-shirt sizes, Fibonacci figures—not man-hours

- That there might be a discussion ahead with the perception of velocity by stakeholders. (It might trigger attempts to micromanage the team, or determine delivery dates: Scrum: The Obsession with Commitment Matching Velocity.)

- That there are useful agile metrics available.

- Start using estimation poker on all required stories.

- Step 7: Explain how dealing with technical debt fits into the game, so that the Scrum team ensures that a fair share of each sprint’s resources are allocated to refactoring.

Tip: When there is (an urgent) release scheduled in the near future—say in 8 to 12 weeks—that needs to be met, and the Scrum team is already on a tight schedule, the initial backlog refinement will likely be not ideal from a Scrum master’s perspective.

However, insisting in such situations on a textbook approach—which inevitably will result in a delay of the release—is likely to cause serious communication problems. The management, and particularly those managers and stakeholders that might have opposed going agile in the first place, might consider their worst fears confirmed. Be pragmatic, and think twice before picking your battles.

Conclusion

Kicking off the agile transition in an organization with an existing product backlog by a thorough refinement session is a proven technique. It is a good exercise to train the new Scrum team on the job in artefacts, ceremonies, and agile principles.

Be careful, though, to practice “Le Scrum pour le Scrum”, particularly when an urgent release is imminent. This might cause unnecessary irritations with stakeholders.