Watch this year’s World Series of Poker as it culminates with the Main Event’s final table on July 16 and 17, and you see a clean, slick, nicely presented event. Thousands of people gather to vie for millions of dollars. They get paid big bucks to wear the logos of PokerStars, 888 and PartyPoker.

Phil Hellmuth is famed for his splashy, costume-wearing entrances. At least one massage girl got carried away last year and went to work on a player’s exposed nipples. This year, there were allegations of card-marking leveled at Martin Kabrhel. Superstar players – guys like Daniel Negreanu and Phil Ivey – have movie-star worthy honeywagons backed up to the casino entrance. They relax in style between tournaments. It’s not unusual for top-tier players to be accompanied by bodyguards while en route to fabulous dinners, private parties and even the card tables.

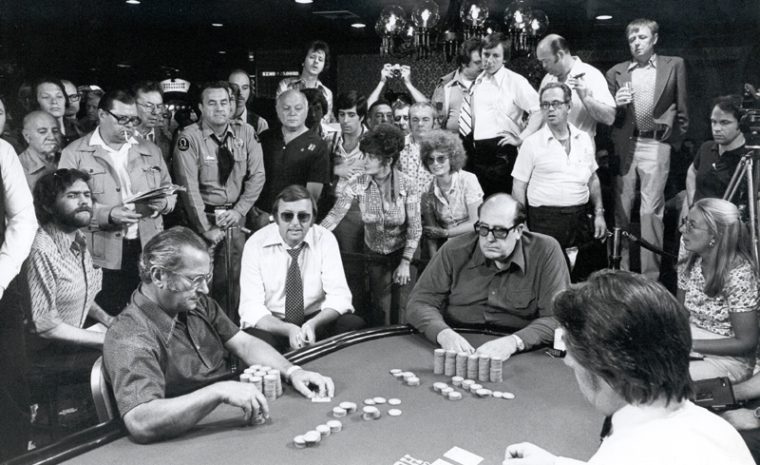

Launched in the 1970s as a set of publicity-generating cash games (the current freeze-out format did not kick in until year-two of the Series), the winner was chosen by the high-flying participants.

But the richest poker tournament in the world, originally held at the now defunct Binion’s Horseshoe in downtown Las Vegas, did not start out that way. Launched in the 1970s as a set of publicity-generating cash games (the current freeze-out format did not kick in until year-two of the Series), the winner was chosen by the high-flying participants. There were only seven of them, but they represented the most daunting poker talent in the world.

These days, winning the World Series of Poker Main Event, with the 2023 first prize expected to be in the $10 million range, requires a combination of luck and skill. Back in the early ‘70s, with a small group of the world’s greatest competing – most of whom came from Texas and the American south — luck played a much smaller role.

Being crowned champion was also less of a big deal.

Being crowned champion was also less of a big deal. In his memoir “The Godfather of Poker,” the recently deceased Doyle Brunson, who participated in the first Series, recalled, “There were 12 players signed up [to play in 1972] but with the cash games so good, only eight of us played.”

That same year, when it came down to Brunson, Puggy Pearson and a splashy Texan by the name of Amarillo Slim Preston, Brunson and Pearson threw the match. They chopped the prize pool and let Slim win. As Brunson explained it to me, “We knew that being named the best poker player in the world would not be good for business.”

Plus, he added, “I didn’t want to embarrass my family. The common working guy looked down on poker.”

More recently, another source told me that Brunson was not crazy about paying taxes on the win, which would be reported to America’s IRS authorities. As per the source, “Slim said that Doyle and Puggy could have their ends and that Slim would take care of the taxes — whatever that meant.”

Last year there was a fear that somebody had fired off gunshots in the tournament room at the Paris casino (one of the places where the WSOP is now held).

Slim went on “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” and talked up poker. He wanted Horseshoe proprietor Jack Binion to fork over money in order for him to mention the casino. Binion refused and Slim kept the Horseshoe out of the conversation. “That pissed me off,” said Binion. “He did a good job with his corny sayings, but he never mentioned the Horseshoe.”

Last year there was a fear that somebody had fired off gunshots in the tournament room at the Paris casino (one of the places where the WSOP is now held). Players rushed for the exits. Daniel Negreanu got trampled and wound up with a bloodied hand. Mike Matusown injured his already tender back (he racked it while sitting in the front seat and going on a fast-accelerating car ride with “playboy of Instagram” Dan Bilzerian).

But the shots were a false alarm. Decades earlier, there was nothing phony about a deal cut at the WSOP to organize the shooting of an American federal judge.

Notorious pot smuggler Jimmy Chagra — the model for Javier Bardem’s character in “No Country for Old Men” — bemoaned the likelihood of a judge known as “Maximum” John Wood living up to his name in an upcoming sentencing. He mentioned that he’d like to see the “son of a bitch” dead. Between hands, hitman Charles Harrelson (father of actor Woody Harrelson) said he would do the deed. They settled on $1 million, for Harrelson to shoot Wood after the trial, which would give Chagra a perfect alibi.

“The man had just killed a federal judge,” said the now deceased Becky. “What would Harrelson have done to Jimmy?”

But Harrelson jumped the gun and killed Wood prior to sentencing. “I nearly puked,” Chagra told Texas Monthly. “It was supposed to be after the trial.”

Nevertheless, Harrelson got his million dollars, paid to him in a cash loaded Pampers box, according to Jack Binion’s sister Becky. She told me that there was no chance of Chargra not paying, even though things did not go quite as planned. “The man had just killed a federal judge,” said the now deceased Becky. “What would Harrelson have done to Jimmy?”

While concentration-enhancing drugs such as Adderall are as common as bottles of Fiji water at today’s poker tables, things were different back in the day. During the 1970s and ‘80s more nefarious drugs were consumed with relative impunity at the down-and-dirty World Series. Famous champ Stu Ungar (a tiny guy who nicknamed his Magnum-worthy penis “The Flashlight”) was such a prodigious user that his collapsed right nostril was noticeably caved as a result of the drug use.

“Not coming down to defend your title is unheard of.”

At the card table, Brunson eschewed Ungar’s nickname of choice, “The Kid,” and was known to call him “Rudolph” in recognition of his sore nose with its red hew. Ungar’s drug use was debilitating enough that the three-time World Series of Poker champion did not come down from his Horseshoe hotel room to defend his crown in 1998, one year after he won his third Main Event (which still stands as a record).

As I was told, prior to the Main Event, by Jim Albrecht who oversaw tournament poker at the Horseshoe, “Not coming down to defend your title is unheard of.”

That year Ungar did the unheard of. Sequestered behind closed doors, he told me that he wanted to play in the tournament but couldn’t get it up to do so. “I showered and got dressed,” he said. “Then I looked at myself in the mirror. I looked terrible. I wasn’t geared up. I wouldn’t have put in a good performance. The year took a toll on me.”

I encountered him while reporting a story about his roller coastering rise and fall. When the article ran, with a photo that showed his collapsed nose to full effect, he griped to biographer Nolan Dalla, “It’ a disgrace what they did. Those cocksuckers. I don’t trust people anymore.”

But Ungar would not have been the only drugged up pro at a Series table. Despite its desert locale, Las Vegas was a place where it snowed year-round. Poker legend Chip Reese had his “disco garage” where blow and high-stakes backgammon were always on the menu. Underscoring the point, 1979’s final table was an all-druggy event. The donnybrook was between an LA public relations man named Hal Fowler and the poker-pro/golf-hustler Bobby “The Wizard” Hoff. Both, let’s say, had their heads a little full.

The Wizard was a “young, cocaine-addicted poker genius” and Fowler, as the big game tightened up, was “popping as many as 20 valiums to calm his nerves.”

The tenor of the action was influenced by which drugs were coursing through a particular player’s bloodstream. In his exemplary book “Cowboys Full,” Jim McManus (who has a fifth-place Main Event finish to his credit) describes the two men thusly: The Wizard was a “young, cocaine-addicted poker genius” and Fowler, as the big game tightened up, was “popping as many as 20 valiums to calm his nerves.”

That said, he must have been doing something right. He became the first non-pro to finish first in a Main Event. These days, with the field drawing thousands (a situation not hurt by the fact that the unchanged entry fee of $10,000 is a lot easier to scrape together today than it would have been in the 1970s or ‘80s), and the need for good fortune playing a major factor, amateurs inevitably make it to the final table and get to take their shots at poker-world glory.

As Jamie Gold, the cocky Hollywood producer and amateur poker player who won $12 million at the 2006 Main Event, put it, summing things up for every home-game hero with big time dreams, “I protected myself and played well but of course I got lucky and I just feel really fortunate that things went my way.”

The latter is an understatement; he got way lucky. The former, alluding to his skills, well, chalk it up to being a bit of a bluff.