A common misconception about conversion optimization is that your work ends when the user converts.

This is a limited way of viewing things, however, and you’re likely leaving a lot of money on the table if this is where you stop optimization efforts.

Customer loyalty is a nebulous concept, but crafting experiences optimized for loyalty reaps many short-term and long-term rewards.

It’s not an easy feat, but this article is designed to arm you with the knowledge and tools to start optimizing beyond the initial purchase conversion, and hopefully, to rack up some repeat purchases and referrals in the process.

How Do We Define Customer Loyalty?

Generally speaking, customer loyalty is defined as the intention and action of choosing a certain brand or product repeatedly instead of other alternatives.

This attitude is measured through a variety of means, namely the customer’s intention to repurchase, the intention of cross-buying (buy another product from the same company), the intention to switch to a competitor (price tolerance), and intention to recommend the brand/company to other consumers.

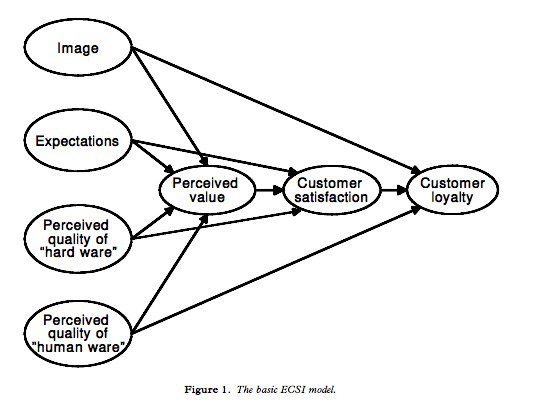

The European Customer Satisfaction Index, a model for understanding customer loyalty (Image Source)

All of those indicators use different instruments to measure customer loyalty, but they’re all getting at the same thing: is this customer likely to continue using our product or even tell others about us?

Customer loyalty is sometimes confused with customer satisfaction, as well as retention.

The differences are small but important.

Retention is the behavioral indicator of loyalty, whereas loyalty is usually attitudinal (though technically retention could be considered behavioral loyalty).

Customer satisfaction is simply an attitudinal measurement of satisfaction for a product, brand, or experience, and may not have anything to do with loyalty or repeat experiences.

Why Optimize for Customer Loyalty?

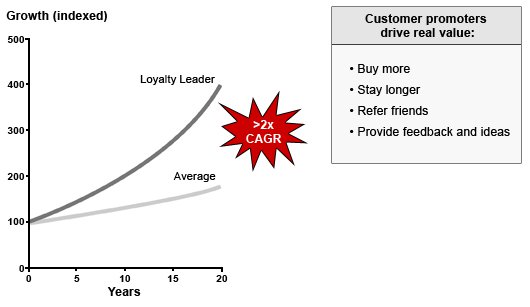

There are various statistics out there on the value of repeat/loyal customers.

For instance, it’s been shown that after one purchase a customer has a 27% chance of returning to your store. But if you can get that customer to make a second and a third purchase, they have a 54% chance of making another purchase.

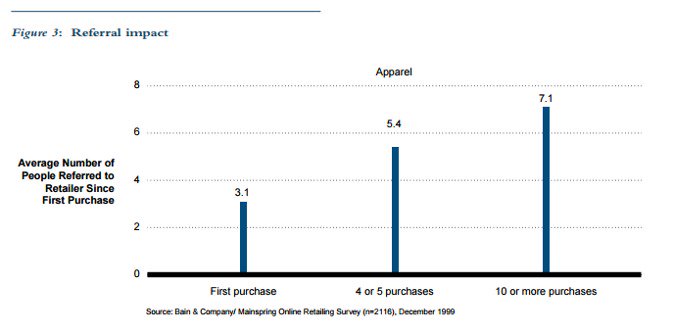

Loyal customers tend to spend more, purchase more often, and tell more people about your brand.

To most businesses, customer loyalty is worth a lot of money.

Every study I’ve seen points towards the undeniable ROI of customer loyalty. Yet still, marketers devote very little in terms of resources to optimizing for loyalty.

Why is this the case?

First, increasing customer loyalty doesn’t just fall within marketing – it’s an enterprise wide responsibility. As Forrester put it, “Best-in-class loyalty strategies require input and participation from all customer-facing departments in the organization — including customer service and customer experience — to be truly effective.”

Second, the costs of a loyalty strategy are easy to account for – it’s easy to add up costs for support, technology, campaign costs, etc.

But because of the long-term nature of retention and loyalty, it’s harder to measure the outcomes, and therefore, it’s harder to prove the ROI up front.

6 Research-Backed Tactics for Increasing Customer Loyalty

Though improving customer loyalty still is, indeed, very much an art form, there has been a lot of research done on the subject, too.

While the following suggestions are back in research, the exact execution of the following advice will be specific and will require testing and tweaking to make it work for you.

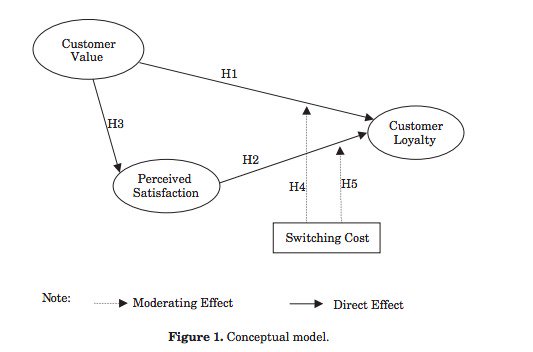

1. First Ask Yourself, “What’s the Cost of Switching?”

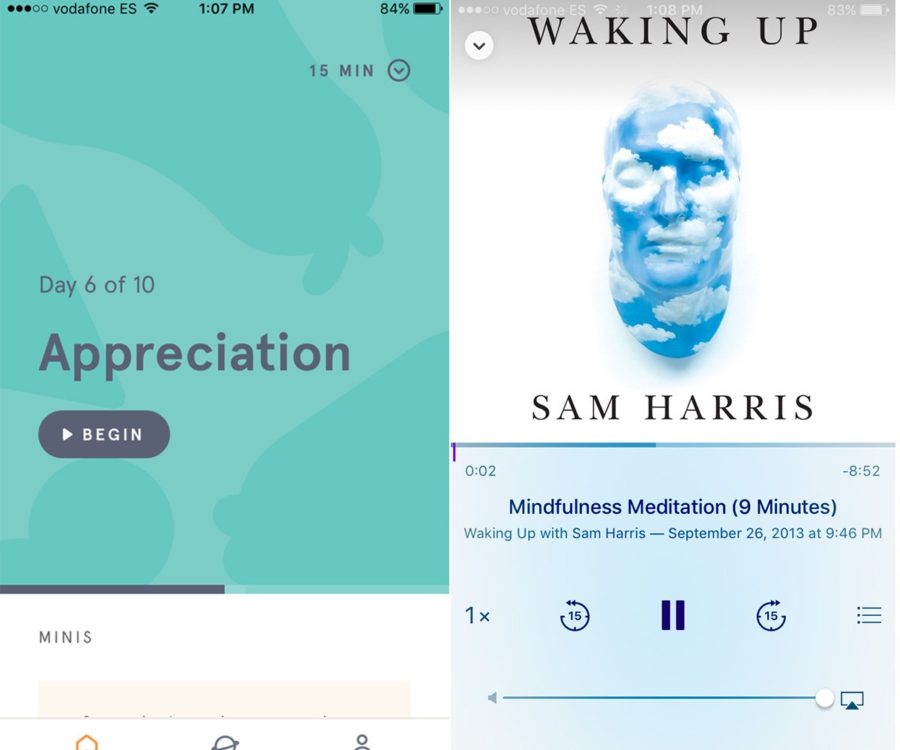

If you’re the purveyor of a meditation app that costs $5 per month, the cost of switching is incredibly low and the competition is plenty. You should worry about optimizing for customer loyalty.

If you’re an optimizer for a required service in an environment of limited or zero competition, let’s say the DMV, then customer loyalty is not very relevant.

The ROI of your investment in customer loyalty, therefore, depends on your ability to influence it in the first place, as well as the potential effects of a hypothetical increase.

If you create a loyal customer for your detergent brand, for instance, you have a lifetime customer.

But if you create a loyal customer for your social media management tool or your brand of shoes, you have a lifetime customer as well as the high probability of word-of-mouth referrals.

That said, the advice for increasing customer loyalty follows the same party lines that conversion optimization or user experience advice follows.

If you take the advice, you risk almost nothing (as long as you have a solid experimentation program), but you may just improve the user experience. An improved user experience tends to have many positive effects, one of which is increased customer loyalty, but another entirely is that you may increase your conversion rate.

2. Reduce Customer Effort

One of the greatest ways to improve user experience as well as customer loyalty is to reduce cognitive load and makes things easier for your users.

In fact, a Harvard Business School study found that reducing the effort customers have to exert is the number one factor in creating customer loyalty.

This helps to drive repeat behavior, too, and habit is important in creating customer loyalty (as we’ll discuss later). If an app is easy to log into and use, I’m more likely to become a loyal user than if it were an arduous task every time I tried to use it.

This ease of use contributes to what A.G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin consider a “cumulative advantage,” which they define as “the layer that a company builds on its initial competitive advantage by making its product or service an ever more instinctively comfortable choice for the customer.”

Make it easy to try, buy, and use your product.

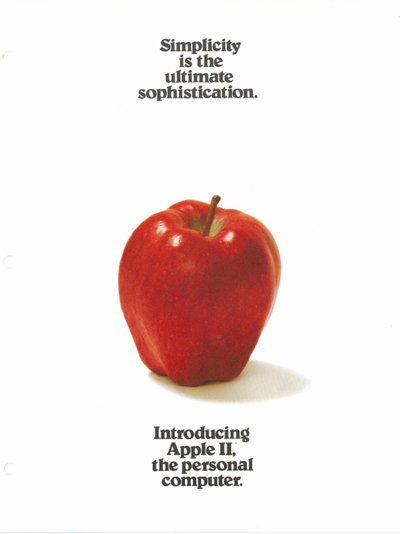

Keep it Simple; Design for Simplicity

The easiest way to implement this is to adhere to the simplicity principle. Never overcomplicate things, and always try to keep things as friction-free as possible.

A.G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin put it very well in an HBR article:

“Remember: The mind is lazy. It doesn’t want to ramp up attention to absorb a message with a high level of complexity.

Simply showing the water resistance of the Samsung S5—or better yet, showing a customer buying an S5 and being told by the sales rep that it was fully water-resistant—would have been much more powerful.

The latter would tell fast thinkers what you wanted them to do: go to a store and buy the Samsung S5.

Of course, neither of those ads would be likely to win any awards from marketers focused on the cleverness of advertising copy.”

We’ve talked about this very much in regards to conversion optimization and website design, but this heuristic is very apparent to anyone in user experience, usability, product design, advertising or sales.

Make things simple, and people are more likely to do them or understand the message you’re trying to convey. Remember the conversion optimization/copywriting advice: clarity trumps persuasion.

Processing Fluency, Habit, and Making the Choice Easy

Behind this message of simplicity is really the science of “processing fluency.”

Processing fluency is the ease with which information is processed. Of course, many elements go into this including visual design, messaging, and intuitive interactivity.

But one thing that is often forgotten is that process fluency is also a product of repeated experience. Basically, the more times we have the experience, the easier it is for us to process.

A.G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin talk about this in HBR:

“A driving reason to choose the leading product in the market, therefore, is simply that it is the easiest thing to do: In whatever distribution channel you shop, it will be the most prominent offering.

In the supermarket, the mass merchandiser, or the drugstore, it will dominate the shelf. In addition, you have probably bought it before from that very shelf.

Doing so again is the easiest possible action you can take. Not only that, but every time you buy another unit of the brand in question, you make it easier to do—for which the mind applauds you.”

Everyone can relate to this. The first place I go to shop is Amazon, because I’m used to it and it’s easy. The first place I search is Google, because I’m used to it and it’s easy. It’s only if I go to my first choice and am not able to complete a task that I seek out other options.

At least, that’s the way it is in relatively straightforward, rote tasks, or in purchasing products that are commoditized.

In larger and more complex purchases (think B2B here), there’s a whole lot more reflection and contemplation. With SaaS and the lack of contracts (for the most part), this contemplation and comparison doesn’t stop; we can choose to end our relationship with Marketo and choose HubSpot at any point in time. Therefore, it’s in products of this nature that customer loyalty becomes supremely important.

We can say the same thing for B2C products, for example, HeadSpace. You don’t need a meditation app to live, and if you want one, there are many alternatives available. So it comes down to this: how loyal are you to Headspace? How much do you love the product and how easy is it to stick with it?

There are tons of choices when it comes to some B2C apps, including using none of them.

Same goes for products like Duolingo, CXL Institute, or essentially any restaurant or coffee shop you’ve ever been to. A bad experience can ruin the whole thing, and you can choose to quit entirely or move to a competitor. It’s products like these that really need to invest in optimizing for customer loyalty, not just acquisition.

And that’s what brings me to the next point: once we capture the attention of a user, we must do everything we can to repeat the experience. We need to bring them back and attempt to create a habit.

3. Repetition is Important, Design for Habit

Capturing users out of the gate is important, so is making it easy to use your product (or buy) for the first time. But none of that means much if you can’t keep customers around. If they try once, and leave, that’s a massive leak in your funnel and a huge hole in your business model.

That’s intuitive from a marketer’s standpoint, though. You know the value of retention. What you don’t think about is the fact that retention begets retention. The more someone uses your product, the more likely they are to continue using it.

Here’s how A.G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin put in HBR:

“Each time you choose a product, it gains advantage over those you didn’t choose.

Meanwhile, it becomes ever so slightly harder to buy the products you didn’t choose, and that gap widens with every purchase—as long, of course, as the chosen product consistently fulfills your expectations. This logic holds as much in the new economy as in the old.

If you make Facebook your home page, every aspect of that page will be totally familiar to you, and the impact will be as powerful as facing a wall of Tide in a store—or more so.”

This is where the startup obsession with DAUs, engagement, and finding and optimization for the Aha moment come into play.

It’s one thing to acquire a user. But once they’re there, you need to do everything in your power to encourage activation. You need to get them back in your product, and often.

How to Design for Habit

All that is to say: optimize for habit.

This is a wildly deep, complex, and nuanced topic. There’s no one easy answer or a step-by-step guide to designing for habit (again, if there were, the field of product management, growth, CRO, etc., wouldn’t be as important).

Nir Eyal’s Hook framework is a popular way to model habit (Image Source)

The best possible end goal here is that choosing your offering becomes an automatic choice, something a customer doesn’t even consider. To do that isn’t easy. Luckily, there are lots of smart people writing and teaching about how to do that.

While a lot of this is a function of product management, making your product addicting can be assisted by loyalty programs and gamification.

4. Implement Loyalty Programs and Gamification

Most of the time, at least in the software space I’m most familiar with, habit is largely a function of the product itself (as well as messaging and engagement to a lesser extent).

But in more traditional retail as well as ecommerce, you may be more familiar with loyalty programs. Indeed, in software products and apps, some of these principles are adopted in the form of gamification.

These programs can work, but must have the critical pieces in place first. Namely, if your product sucks, you can’t patch on a loyalty program or some gamification and hope to solve it.

There are many different ways you can structure your rewards programs, and often it depends on your business. Three ways:

- Points (like Duolingo “gems”)

- Achievement (like Duolingo streaks)

- Competition (like Duolingo scoreboards)

There are many ways to structure a loyalty program (Image Source)

Implementing a successful rewards program isn’t easy; there are a lot of moving pieces. Also, as I mentioned, you can’t expect to just patch on a loyalty program and have it solve retention problems.

5. Invest in Fanatical Customer Support

Customer support, customer success, customer experience: no matter the name, just care about your customers.

There are many blogs, books, and speakers out there, none of which will advise you against that sentiment. Yet it’s so rare to find a company that actually exhibits customer-centricity (except for Amazon, and it’s no wonder they run the world).

We’ve written about this before, so I won’t brood on it too much. Instead, I’ll just do a brief summary of some tactical advice for crafting a better customer experience:

- Make it easy for customers to complain.

- Listen to complaints and fix problems in your business.

- Work tirelessly to fix the problems of your most passionate and angry customers.

- Fix problems as quickly as you can.

- Wow your customers. Go overboard.

- When all else fails, respond from the top.

6. Shared Values Lead to Customer Loyalty

Peep Laja, founder of CXL, wrote quite a while ago about the value of shared values. They’re an incredibly powerful mechanism for triggering long term customer loyalty (as long as the values are real and important).

What are consumers really loyal to? This has been studied quite a bit, one key study found people are not loyal to companies, they’re loyal to what the companies stand for.

As Aaron Lotton put it, “We saw that emotional attachments to brands certainly do exist, but that connection typically starts with a “shared value” that consumers believe they hold in common with the brand.”

In 1983, Harley-Davidson was almost going out of business. By 2008 the company was valued at $7.8 billion, being one of the top brands in the world. Central to the company’s turnaround and success was Harley’s commitment to building a brand that stands for something. Its customers organize around the lifestyle, activities, and ethos of the brand.

Despite its weakening pull on younger demographics, it’s undeniable that Harley-Davidson customers feel a shared sense of values with the brand.

This famous commercial (well-known in advertising classes, at least), shows that perfectly:

“Do You Know the Enemy?”

A very common rule in branding and positioning is that you should define the enemy.

Coming out of the gates, HubSpot made it clear that disruptive advertising was the enemy. The solution: their inbound approach.

Similarly, Apple has consistently staked a strong position as the brand favored by young, the hip, and the rebellious, which makes Microsoft, well, the opposite:

This is really a continuation of the same principle wherein humans want to feel like they’re part of a group. One of the easiest ways to establish that feeling is by establishing and in-group vs. out-group mentality.

We talked about this a lot on a recent post covering Cialdini’s 7th Principle of persuasion: unity.

Creating an outgroup is sort of a reverse-granfalloon tactic.

Instead of appealing to a sense of group cohesion, you position you and your group against another one, real or imagined.

While this has been played out poorly many times in history (cults use this to indoctrinate members and isolate them from the world), it’s also an effective positioning strategy. A great example of this is Chubbies and their consistent antagonism towards cargo shorts, pants, and the office.

By positioning themselves against these ideals, they form their own group cohesion and identity (people that wear Chubbies love fun, the weekend, and short and funny shorts).

How to Measure Customer Loyalty and Optimize Over Time

There are many ways to measure customer loyalty, some more complicated than others.

If you’re a market researcher or academic, you’re likely familiar with the more esoteric varieties. For instance, this study from the International Journal of Market Research used five customer loyalty indicators:

- Customers’ overall average rate of buying a variant in the analysis period (typically a year).

- A direct index of repeat buying (the percentage making at least two purchases).

- The incidence of 100%-loyal buyers.

- The SCR (the variant’s share of its customers’ total category requirements).

- The duplication of purchase measure: the percentage of the customers of, say, the large pack size in the analysis period who also bought the small size in the same period.

This approach is, of course, quite robust and extensive in its behavioral and attitudinal measurement. But I’ve found that when something requires this degree of knowledge, complexity, and obstacles, it’s rare that it will actually be done.

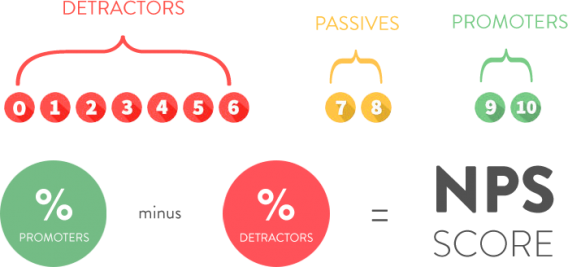

Therefore, I propose the easiest way for a company of any size to measure customer loyalty is to use NPS. Though it has downsides (as any metric does), it is simple and you can compare it across companies and industries to get a good idea of where you stand. More importantly, you can measure it longitudinally and compete against yourself to improve your NPS score.

NPS has been shown to correlate strongly with customer loyalty, giving you an accurate indicator of that metric.

The bonus of NPS is that it can be combined into your CRO/experimentation to provide further insights on your efforts. Here’s how John Ekman, founder of Conversionista, put it in a comment on a previous blog post:

“If you are able to connect the NPS survey to an actual experiment, such as an A/B test or a personalization tactic, you will get additional data out of your experiment.

When people exit the experiment you can measure how much the experience affected their NPS score.

And this data will not only tell you how many clicked or bought, but additional qualitative data on WHY they did so.”

Conclusion

Optimizing for customer loyalty is one of the most important things you can do, yet it’s also one of the most challenging.

For one, it’s tough to make the business case for customer loyalty initiatives because of the long term nature of the ROI. This is certainly true of experiments where the main goal is optimizing for retention: it takes a long time to determine the results.

Second, while there is a ton of research regarding loyalty, there’s a lot of wiggle room on how exactly you execute the strategies. So yes, reduce cognitive load and make your messaging and product simple. Invest heavily in customer support and experience. Stand for something. Reward loyal customers.

But how you do those things is entirely up to you.

Read more: How to Build Customer Loyalty with a Thank You Page