Every project, product, and business starts with an exciting new idea. But some ideas are unrealistic.

Before you invest time and money, you need to make sure that your plan is practical and worthwhile. A feasibility analysis helps you systematically assess the plan, identify roadblocks, and check you have the resources you need to succeed. Here’s our guide to an effective feasibility analysis.

Key Highlights: Feasibility Analysis

- Definition: A feasibility analysis evaluates if a business idea or project is practical and likely to succeed. It ensures the plan has the necessary resources and potential profitability.

- When to Conduct: Useful before starting a major business, product launch, or event, especially when there are significant investments or complexity involved.

- Main Purpose: To assess financial, market, operational, technical, and legal factors to determine if a project will succeed without major obstacles.

- Core Steps:

- Preliminary analysis (quick scan for obvious issues)

- Gather financial information and conduct ROI analysis.

- Study market demand and competition.

- Assess operational and legal feasibility.

- Outcome: A recommendation to move forward or stop, ensuring you avoid costly mistakes and focus on viable initiatives.

What Is a Feasibility Analysis?

A feasibility analysis (also known as a feasibility study) is a process of evaluating an initiative to determine if it is not just feasible but also viable. That initiative could be:

- a project

- a product or service

- a business idea

The goal of a feasibility study is to prepare the data needed to make informed decisions about whether or not to go ahead with an initiative. The most important questions are:

- Do you have the necessary resources to make the initiative successful?

- Can the initiative be profitable or offer a positive return on investment (ROI) in other ways?

- Are there any major, unavoidable obstacles that will prevent success?

A good feasibility study is objective, rational, realistic, and based on data rather than assumptions.

When To Do a Feasibility Study?

A feasibility study is useful when you’re starting a business, launching a product, acquiring a business, or planning an event, construction project, or marketing campaign. It is especially useful for a complex project that requires a lot of investment.

The feasibility study process takes place after the initial planning stage but before the work begins. You should already have a detailed plan laid out, perhaps in a project pitch or business plan.

Who Conducts a Feasibility Study?

A feasibility study can be conducted by senior managers, project managers, product managers, accountants, consultants, entrepreneurs, or anyone embarking on a project. You could even conduct a feasibility study informally for a personal project like a wedding or home renovation.

Purpose of a Feasibility Study

The overall goal of a feasibility study is to determine whether a proposed project or initiative is viable and will produce enough value to justify the costs involved. In addition, a feasibility study aims to:

- test the financial practicality of a project

- identify potential risks, obstacles, and constraints

- evaluate demand, competition, and market conditions

- highlight technical and operational deficiencies

Elements of a Feasibility Study

There are six factors to consider when conducting a feasibility study.

1.Technical Feasibility

Technical feasibility is about whether you have the technology, equipment, and technical skills or knowledge needed to make the proposed plan a success. For example, if you have an idea for an app but you can’t afford to hire a developer, it probably isn’t technically feasible.

2. Financial Feasibility

Financial feasibility (or financial viability) is about return on investment (i.e. the profitability of an endeavor relative to the cost) as well as financial risks, opportunity costs, and cash flow.

For instance, if you’re thinking about opening a new location for your retail business, will it bring in more value than improving an existing one? Do you have enough cash to make a deposit on a new property and set it up? If the new location doesn’t succeed, could it jeopardize your entire business?

If you’re thinking of starting a business, you’ll need to identify your start-up costs, operating costs, pricing, and projected sales figures. You should also consider:

- how long will it take to recoup initial costs.

- how you will finance the business until you make a profit.

- how you will meet financial obligations if you don’t become profitable.

3. Market Feasibility

Market feasibility is about whether or not the proposed project is a good fit for the current market. It doesn’t matter if the idea is technically and financially feasible if it just doesn’t make sense in the current market. To establish market feasibility you need to conduct market research and competitor analysis. Try to get a good idea of the demand for your proposed product or idea.

For example, if you have a yoga studio and you want to start selling branded yoga clothing, is that something your customers want? Is yoga clothing a robust trend? Which other brands of yoga clothing are available? Can you compete on price, quality, convenience, or design?

4. Operational Feasibility

Operational feasibility is about whether your organizational structure and logistical resources can support the proposed project. Do you have enough staff? Does the plan make logistical sense? Do you have the structures to optimize resource allocation?

For example, if a hospital wants to take on additional surgical patients, there need to be enough nurses, administrative staff, cleaners, elevators, operating rooms, recovery rooms, waiting rooms, and even parking spaces to accommodate patients safely.

You should also consider scheduling feasibility (a subcategory of operational feasibility) which is really just the question ‘Can you get the project done by the deadline?’

5. Legal Feasibility

Are there laws or regulations that prevent your project? Do you have access to sufficient legal and compliance advice? Are you missing any permits or licenses that you need to proceed? Are you placing your organization at risk of legal action ? These are some of the questions you need to ask to assess legal feasibility.

How To Do a Feasibility Study in 8 Steps

At face value, a feasibility study is straightforward. Simply ask, “Is this plan feasible?”. But complicated projects tend to have lots of moving parts. An effective feasibility study digs into the nitty gritty to expose every obstacle. Here’s our step-by-step guide to conducting a comprehensive feasibility study.

Step 1: Do a Quick Scan

Before you get started, make sure the initiative is laid out clearly in a pitch or project plan so you have all the details you need. Do a quick preliminary analysis to identify any obvious, unavoidable obstacles. Perhaps another company has a patent on the product or the project will take so long to complete that it won’t be worth it. Speak to stakeholders to see if they can see any glaring problems.

Look at the project through three lenses.

- Project-level obstacles e.g. budget or skills shortage

- Organizational-level obstacles e.g. poor marketing or training capabilities

- External obstacles e.g. lack of demand or regulatory challenges

If you find a major issue, abandon the feasibility study until the plan is reworked.

Step 2: Set It Up

After your preliminary analysis, figure out how much time and money you have for your feasibility study, what resources are available, and which stakeholders need to be involved. Do you need to create a feasibility study report? If so, who will read it and what format will it need to be in?

Use this information to determine the scope, budget, and timeline for the analysis. This includes identifying areas that can be excluded. For example, market feasibility may have already been assessed before the idea was pitched. Make a note of any key questions you want to answer.

Step 3: Gather Financial Information

Make a list of all expected costs and revenues associated with the new project. Try to include exact figures and timings wherever possible.

If your initiative needs funding, research whether funding is accessible. Speak to potential investors, lending institutions, or financial advisers to find out the cost and conditions of that funding.

If the proposed project will be conducted by an organization, get a good sense of the organization’s current financial situation including outstanding debt and available capital and assets.

Step 4: Do The Math

Here are some useful calculations for assessing the financial feasibility of a proposed project.

i) Return on Investment (ROI)

ROI is a measure of the profitability of a project or investment. It measures net income relative to the cost of the initiative. To calculate ROI, you will need to research all the costs involved and make some assumptions to estimate profits.

A positive ROI is an indication of financial viability but it is a good idea to compare the potential ROI for the initiative you are assessing to the potential ROI of other potential initiatives or investments.

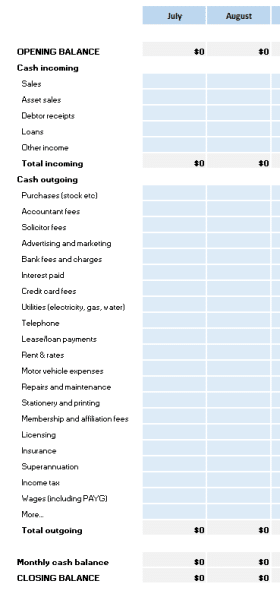

ii) Cash Flow Statement

Positive ROI looks great on paper but it is irrelevant if you don’t have the cash flow to cover expenses as they arise. Create a cash flow statement that lists your estimated opening and closing balance, as well cash incoming (e.g. sales and loans) and cash outgoing (e.g. wages, rent, legal fees) for every month of the project or the first year of a new business.

Estimate how long the business can survive without making a profit. Make sure the business can meet its financial obligations throughout the project lifecycle.

You may want to supplement your cash flow statement with a projected income statement.

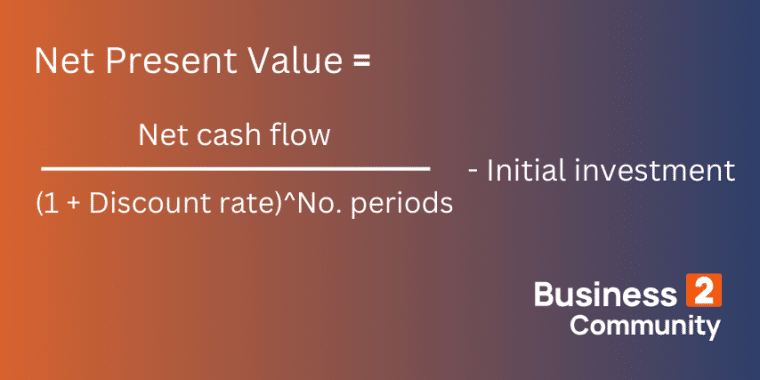

iii) Net Present Value

Net present value is the projected return on an investment adjusted to reflect the present value of money. It estimates the total amount of money a project will generate in its lifetime in today’s dollars.

It is a profitability metric that answers the question: Will the income generated by this project exceed the upfront investment? A positive NPV means the project is expected to be profitable.

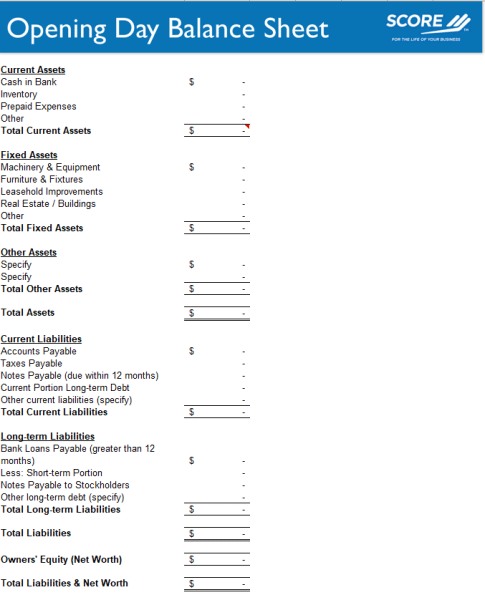

iv) Opening Day Balance Sheet

An opening day balance sheet is a snapshot of your business’s financial position the day you open your doors, accounting for start-up expenses, pre-operating expenses, and initial capital resource purchases. It lists all assets and liabilities.

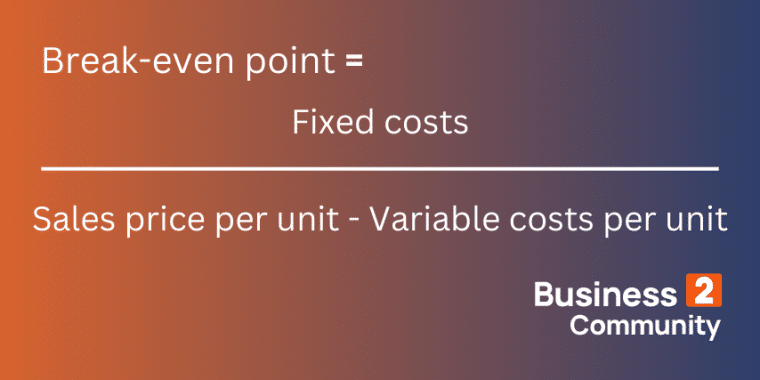

v) The Break-Even Point

A break-even point is the point where your revenue equals your costs and there is no profit or loss. Knowing your break-even point can help you understand the conditions required to make a profit including minimum sales volumes and prices and maximum operating costs.

Step 5: Study The Business Environment

If you are launching a new business, product, or marketing strategy you need to assess:

- customer demand and market potential

- your unique selling point (USP)

- competitors and their USPs

- available market share

- the trajectory of the market

To conduct a competitor analysis, make a list of your competitors. Note down relevant details like pricing, where the product is available, review scores, marketing strategies, and features or characteristics they are known for. Consider how your initiative will compete.

You can conduct primary market research using a market survey and focus groups or, if your resources and requirements are more limited, study secondary market research including reports from industry associations or consulting companies like McKinsey. You can also conduct informal market research by speaking to others in your industry or consuming products and services from potential competitors.

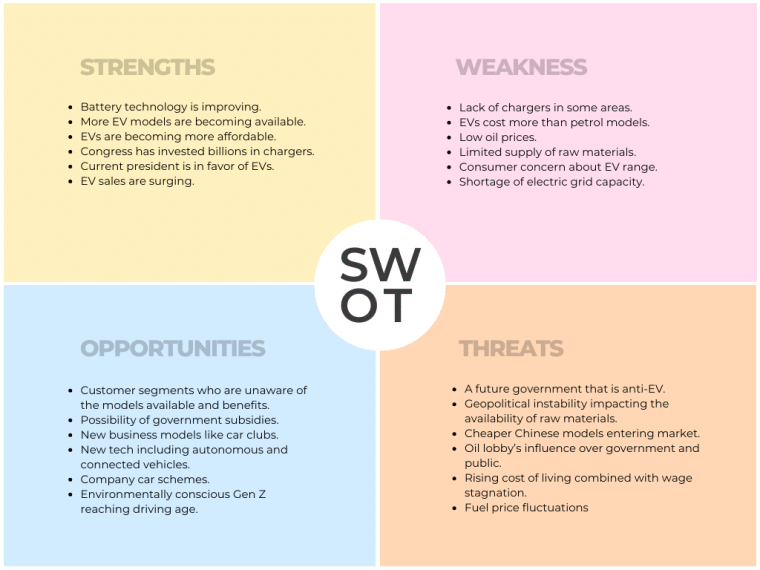

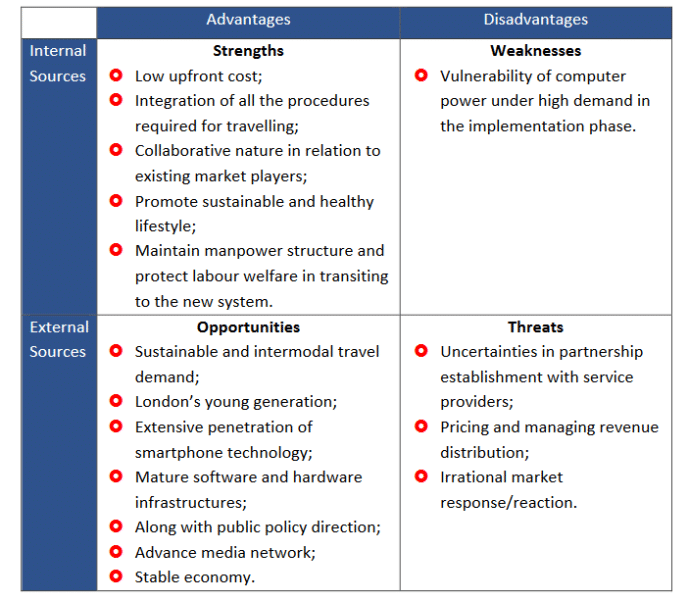

You may find it useful to do a SWOT analysis to assess your organization’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. The example below use SWOT to assess an electric vehicle company.

Step 6: Do a Needs Analysis

A needs analysis is a systematic process of assessing a system or organization to identify deficiencies and find solutions.

‘Needs’ in this context are opportunities for improvement or gaps between the current state of things and the ideal state. The purpose is to figure out the steps required to close the gaps.

First, picture the ideal version of the initiative including the ideal:

- time frame

- equipment

- staff

- skills and experience

- organizational structures

- premises and geographic location

- network and relationships

- logistical systems e.g. supply chain

- brand reputation

Second, make a note of the actual situation. What will you be working with when you launch the project? Identify the “gaps” between the real and ideal situation. Can they be resolved? If not, how will those gaps impact the outcome of the project?

Step 7: Think Technical

Depending on the project, it may be useful to speak to subject matter experts to ascertain the technical feasibility of your plan. That might be your IT team, product managers, or a company from whom you are considering buying technical products.

Useful questions include:

- What are the technical resources required?

- How reliable is the technology we want to implement?

- Are we investing in technology that will soon become redundant?

- Will the technology be more affordable in a few years?

- How long will it take to train staff, suppliers, or customers to use the technology?

- How easily can we solve technical problems if they arise, and at what cost?

- How will equipment impact the work environment e.g. noise, space, and electricity use?

Step 8: Think Legal

If you have an in-house legal team or an external legal adviser, it’s time to get them involved. It’s also a good idea to talk to people who have done similar projects. You can get information about industry-specific legal requirements from your industry association or reliable online resources like government websites.

Think of this step as a is risk assessment. Issues relating to supplier contracts, organizational structure, insurance, data compliance, litigation, consumer rights, intellectual property, tax obligations, and zoning laws are all potential risks.

Remember, some initiatives will fall under more than one jurisdiction i.e. municipal by-laws, state law, federal law, and the laws of another country if your project is global.

Step 9: Make a Decision or Recommendation

Once you’re finished conducting a feasibility study, it’s time to answer the question, “Is this initiative feasible?“. You should now be equipped to make informed decisions or prepare a comprehensive report for decision makers.

A feasibility report may include the following sections.

- An executive summary

- A description of the initiative

- Financial projections

- An outline of technical, market, legal, and operational feasibility

- Summary of major roadblocks and possible solutions

- Your recommendations i.e. give it the green light or pull the plug.

What To Do Next

If the feasibility study concludes that the project is feasible, you can start. It’s a good idea to use the analysis in the feasibility study to improve your project management, mitigate the project’s weak points, and maximize your return on interest.

If the project is not feasible, you may choose to revisit the plan and devise an alternative that resolves the problems with the original version. Once you’ve got a new plan, you should repeat the feasibility study or at least get feedback on the new idea.

Feasibility Study or Analysis Examples

Let’s take a look at two real feasibility studies.

Example 1: Ice Cream Manufacturing

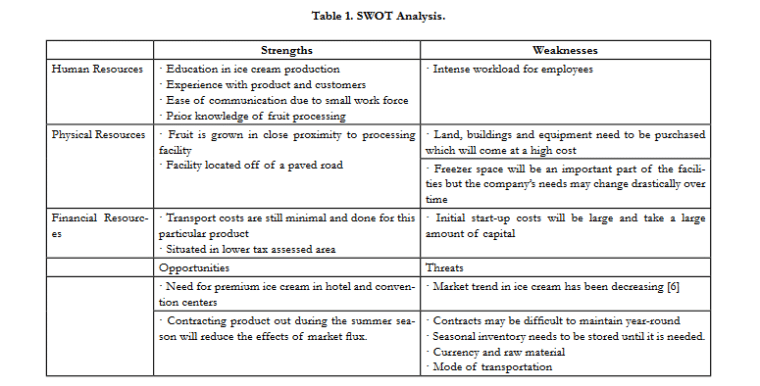

This feasibility study evaluates an idea for an ice cream manufacturing business in Ethiopia. Here are the key findings.

Market Feasibility

Most competitors are local businesses offering homemade ice cream on a small scale. There is a low barrier to entry for new competitors. Ice cream is price elastic and it is easy for buyers to switch brands. Consumers are not brand-loyal and demand is seasonal.

The strategy is to create a premium brand that can command higher prices and target bulk buyers, including upscale hotels, restaurants, and convention centers. The target market are more brand-loyal, more likely to purchase off-season, and poorly served by existing producers.

Operational Feasibility

A location for the manufacturing plant is identified based on access to raw materials, utilities, labor, road transport, and other infrastructure. The strategy to sell in bulk makes delivery logistics more straightforward. A freezer van will need to be purchased for distribution.

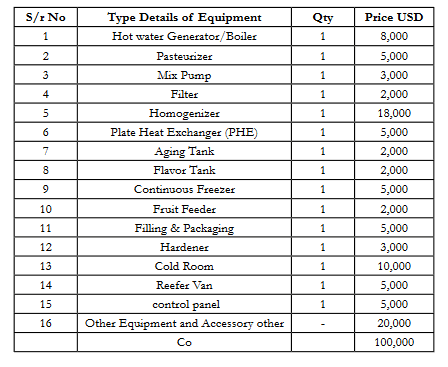

Technical Feasibility

The analyst is a chemical engineering graduate student who has the skills needed for ice cream production. The production process is laid out clearly in the report. A considerable amount of equipment will be required.

Legal Feasibility

A building permit will be required for the plant. The building will fall under both agricultural and commercial tax designations. The floor plan for the proposed building meets Public Health regulations. A representative will need to inspect the building.

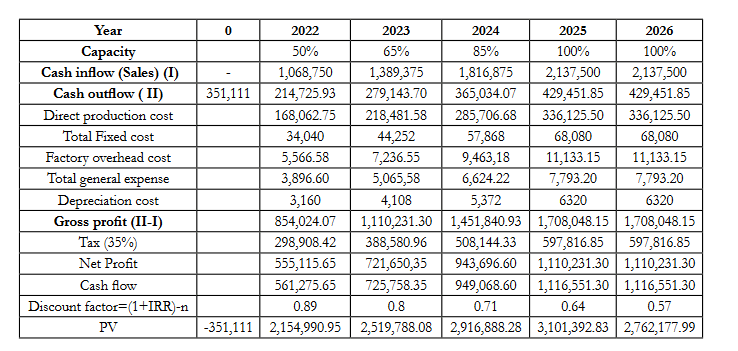

Financial Feasibility

The start-up costs for this business are very high. The report includes plenty of financial data including a price list for equipment, the annual cost of raw materials, and lists of variable and fixed costs.

The ice cream will be sold for $1.25 per 250ml tub in batches of 250 liters. The plant will eventually produce six batches/day, 300 days/year. Therefore the annual capacity is 450k liters. As you can see in the cash flow chart, the plant will not operate at full capacity until year three.

The study finds that net present value for the project is positive and the payback period is under a year. These are strong indicators of financial viability.

SWOT Analysis

The report includes a SWOT assessment which notes the high start-up costs, a decrease in the popularity of ice cream, low transport costs, and the analyst’s technical ice cream production skills.

Report Conclusion

The report concludes that the business idea is a good proposition for investors with the required capital.

Example 2: MaaS-London

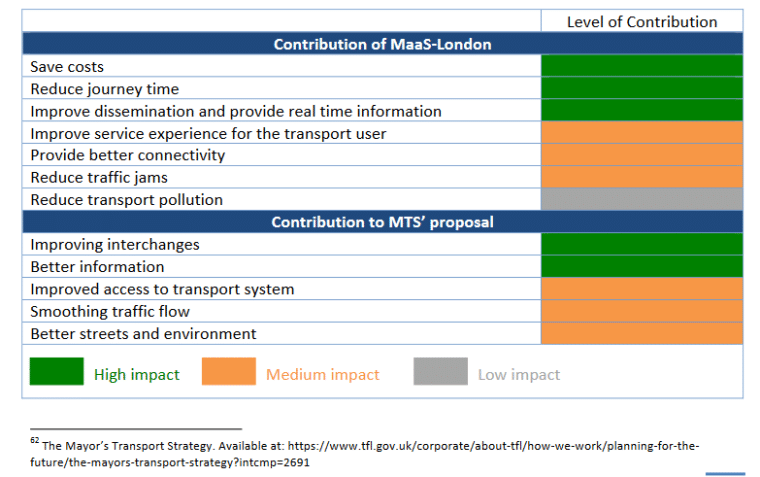

This feasibility study analyzes MaaS-London (i.e. Mobility as a Service-London), a proposed centralized, integrated platform for intermodal journey planning, booking, and payment in London, England.

Stakeholder Buy-In

The biggest hurdle for MaaS-London is the buy-in of all stakeholders. The model should satisfy government, workers, businesses, and customers.

- Government: MaaS aligns with the goals of the Mayor’s Transport Strategy (MTS), as depicted below, including reducing journey time and traffic jams.

- Transport workers can continue in their current roles or be retrained for different roles in the proposed system. Vacancies will also be created for workers to operate the new platform.

- Private transport companies such as taxis will gain access to a larger market of people who can make intermodal journeys more easily.

- Customers will gain access to intermodal transport links which will reduce cost and journey time. Londoners (the target market) are already accepting new modes of travel such as car sharing which suggests they may be open to the proposed system.

Technical Feasibility

MaaS is not a new technology but an integration and expansion of existing tools which is feasible but will require upfront system development costs. It will be challenging to create partnerships with private businesses and link the platform with ride-sharing platforms.

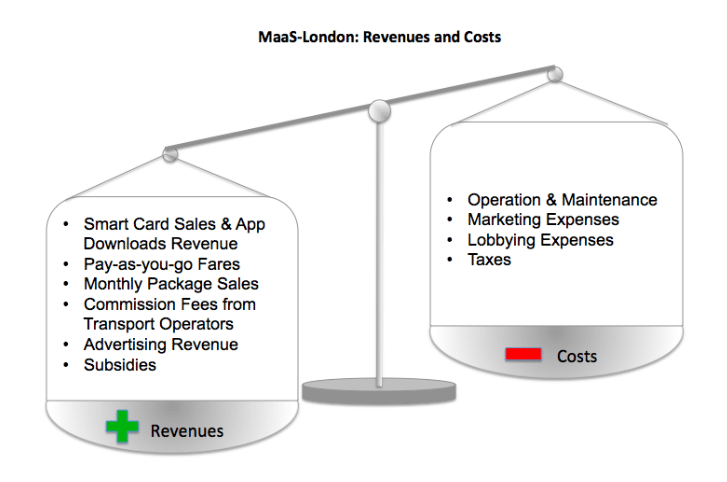

Economic Feasibility

Complex fare structures from a multitude of operators will need to be integrated into a single billing system. This will create an upfront research and development cost. There will be lobbying and marketing costs to get the project going. However, the anticipated revenue will outweigh the costs.

In the long run, economic feasibility will be demonstrated by cost savings for consumers and government agencies.

SWOT Analysis

The strengths of the project include relatively low upfront cost. Weaknesses include the potential overburdening of the system in the early stages. Opportunities include demand for sustainable transport and threats include uncertainties regarding partnerships with service providers.

The Recommendation

The project is feasible but only if key stakeholders are on board. If the right people are on board, it should go ahead.

Tips For a Successful Feasibility Study

Here are some tips for conducting a feasibility study that is smooth and effective.

- Don’t be afraid to say no. Some projects won’t work or just aren’t worth it. It’s far better to be the bearer of bad news at the start than to see time and energy wasted on delivering a bad idea.

- Use hard data. Sometimes things seem obvious but the data tells a different story. Hard data is also more likely to convince decision-makers and other stakeholders of your findings.

- Get buy-in from the start. If stakeholders are included in the feasibility study process, they’re more likely to make helpful contributions and take the findings seriously. Transparency and regular updates can help achieve this.

- Leverage stakeholder expertise. Use the resources at your disposal. If someone has knowledge or skills that can help you test the viability of a project, reach out and ask for help.

Feasbility Analysis Is a Powerful Tool – Use It!

When months of planning have gone into a proposal, it seems crazy to abandon the idea.

But it’s far better to ditch a doomed project right at the beginning than to watch it fail, taking money, resources, and missed opportunities with it. Initiatives that seem certain to succeed may collapse over the smallest detail – a cash flow issue, a complaint from the local community, or a scheduling problem. If you conduct a feasibility study, you have a better chance of avoiding failure and convincing stakeholders to buy in.

You’ll also have peace of mind knowing your project is viable on every level.