A storm may be brewing within pension funds in the United States and the consequences could be quite severe for the wellbeing of countless prospective retirees as these institutions have been pouring billions of dollars over the past decade into risky private equity investments that charge high fees for their services.

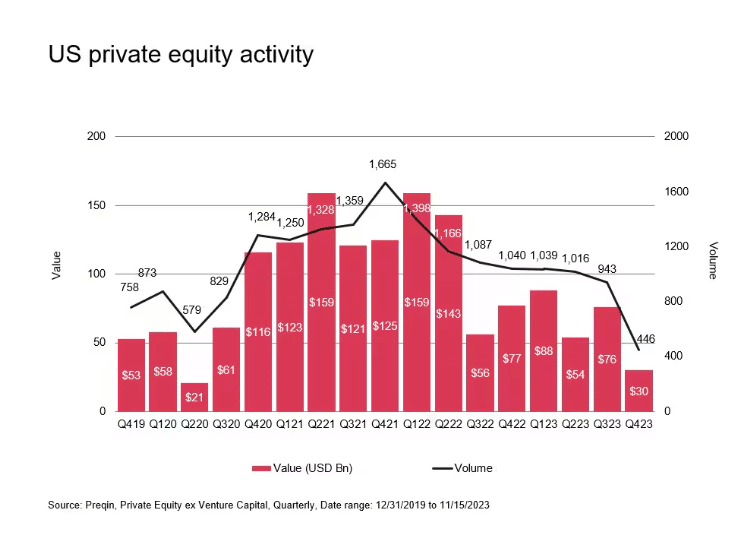

As economic headwinds have intensified in the past few years, the returns and distributions provided by PE firms have dried up and have started to sound alarms across the financial industry. According to PitchBook, a website that tracks the PE industry, these diminished returns became a “major threat to pension plans’ ability to pay retirees in 2023.”

The Pension Fund Crisis in the Making

At the heart of this disconcerting problem lies the opaque methodology used to value the assets held by private equity firms – companies that use investors’ money to buy publicly traded corporations and make them private entities to optimize their businesses, increase their market value, and ultimately cash out of their investments.

Since the assets they invest in now lack a public market that they can rely on to get accurate valuations on their investments, they rely on internal assessments and report the value of their holdings to investors based on their best guesses.

However, there’s no guarantee that, if they are forced to liquidate the assets, they will be able to sell them at the prices they reported.

Also read: How to Invest in Startups in 2024

As a recent study from the Equable Institute highlights, this creates a dangerous lag. Private equity valuations are often inflated during positive economic cycles and are only revised downward months or even years later when reality catches up.

They cited lags of up to six months and commented that these valuations started to drop in 2022, meaning that they were already relatively overstated in 2021.

The result? Pension funds could be sitting on a ticking time bomb, with the full extent of their PE losses from previous years yet to be revealed and incorporated into the funds’ balance sheets accordingly.

Both Public and Private Funds Are Heavily Exposed to the PE Time Bomb

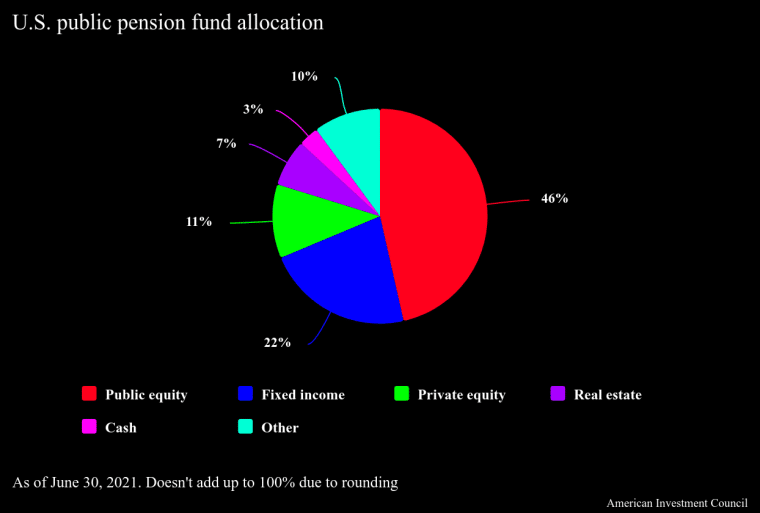

The private equity problem is set to affect a large number of pension funds. According to estimates from Boston College and JP Morgan Chase, around 14% of public pension funds’ assets have been allocated to private equity funds while the largest pensions administered by corporations have poured a similar amount corresponding to 13% of the assets they manage.

In total, American companies and state and local governments manage around $5 trillion in pension money, a significant portion of which is now at risk due to the lower returns produced by private equity firms lately.

Adding to the urgency is the fact that many pension funds were already struggling to meet their future obligations before the spike in market volatility seen in previous years. For years, they have been chasing higher returns by piling into alternative investments like private equity, lured by the promise of higher gains despite the higher fees and reduced transparency of this alternative.

PE Firms Are Expensive, Risky, and Generate Average Returns

The cost of investing in private equity is quite high and has been documented by researchers like Ludovic Phalippou from Oxford University who emphasize that firms in this industry have reaped over a quarter-trillion dollars in fees from pension funds over the years.

Perhaps the most ironic side of the story is that they have generated average returns that barely outperform or end up being in line with public market indexes – which can be accessed at a much lower cost and carry far lower risks.

Moreover, the mechanisms used to negotiate this type of investment by pension funds are typically kept secret as private equity companies are not forced to disclose any of these proceedings or the contracts involved.

Also read: Where To Invest Your Business Assets – Hedge Funds vs Family Offices

This lack of transparency is viewed as another massive problem with these private equity investments by pension funds as conflicts of interest may exist and pensioners should know about them.

“The big picture is that they’re getting a lot of money for what they’re doing, and they’re not delivering what they have promised or what they pretend they’re delivering,” Phalippou commented in his study “An Inconvenient Fact: Private Equity Returns & the Billionaire Factory”.

Despite these significant risks and disadvantages and the unimpressive returns they provide, appetite for PE funds continues to be high, as indicated by Jon Gray, the president of the private equity firm Blackstone, who said in February last year during a call with investors that “the desire for alternatives remains very strong”.

PE Assets Have Been Sold at a Discount of 15% Recently

If private equity returns do indeed disappoint as predicted, the consequences for pension funds could be severe. With fewer assets available to pay for workers’ benefits, funds may be forced to make dramatic cuts to retirees’ payouts, slash funding for important social programs, or demand additional contributions to recoup these losses.

Early signs of this doomsday scenario are already emerging. Some of the world’s largest private equity firms have reported significant declines in earnings while federal regulators have intensified their scrutiny of the industry’s asset valuation practices. Meanwhile, a report from Jefferies Financial Group revealed that private equity assets sold for just 85% of their stated value last year, on average.

To make things even worse, some funds are already taking out loans to compensate for the cash shortage produced by illiquid private equity holdings and to postpone the sale of assets that have probably experienced significant losses and that they may prefer to hold until the market recovers its senses.

The problem is that this may never happen. The market can stay irrational longer than one can stay solvent, the old financial adage goes. One notable example of this trend is the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CALPERS) which, along with several other peer public pension funds, approved taking out loans of around 5% to 10% of its holdings.

Is There a Way Out of the PE Problem?

As the crisis unfolds, attention is turning to potential solutions and protective measures. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is considering new rules that will require private equity firms to provide better disclosures of their fee structures. Meanwhile, some state officials are demanding that public funds stay away from these opaque and expensive investment vehicles altogether.

Also read: How Billionaires Are Made in 2024 – The Tremendous Rise of the Asset Management Industry

In Pennsylvania, the recently elected Governor Josh Shapiro has vowed to move the state’s pension money, which amounts to nearly $100 billion, out of the hands of Wall Street firms. “We need to get rid of these risky investments.”, Shapiro emphasized in a public statement. “We need to move away from relying on Wall Street money managers.”

Similarly, Keith Faber, an auditor for the state of Ohio, recently sounded the alarm on the state of public pension funds and the unethical practice of keeping the agreements made by these institutions and PE firms secret.

Retirement Security at All Cost?

The private equity time bomb is a current reminder of the risks associated with the relentless pursuit of higher returns at any cost. As pension funds struggle to make ends meet amid the illiquidity of their PE investments, some sort of reckoning may be on the horizon and, as usual, workers may end up taking the most severe toll if the house of cards ultimately falls.

At the core of this debate lies a fundamental question: what is the appropriate balance between risk and return when it comes to investing the hard-earned retirement savings of public-sector employees and private-sector workers?

For decades, pension funds have been seduced by PE firms that have promised above-market returns that they have failed to deliver over and over. Although the era of cheap money from central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve may have upended the returns produced by these investment vehicles, the world has changed since COVID-19.

The global economy has now entered a new stage, characterized by stricter fiscal and financial discipline that could erode returns and keep valuations at relatively low levels compared to pre-COVID heights.

As the crisis unfolds, a growing chorus of politicians, regulators, and auditors is calling for a reassessment of this approach.

At the heart of this movement lies the understanding that the primary duty of pension funds is to safeguard the retirement savings of their beneficiaries, not to enrich Wall Street firms or chase returns at any cost.