Native advertising has taken center-stage in the world of digital marketing, and per usual, has fallen under extreme scrutiny. The challenge that most opponents level against the concept (and practice) of native advertising is that it is deceptive to the reader, who might perceive the article as genuine news and not something that’s sponsored.

The foundation of this belief is that news is impartial, whereas native advertising is not. The inherent bias in favor of a company, product, or service that is presented under the guise of news is both wrong and deceptive. That, for one, we can all agree on.

The problem with the arguments posed by opponents of native advertising is the misconception that media – in any circumstance or under any label – are free of bias. The difference between such traditional news reporting and native advertising is that with the latter, there’s actual accountability.

Redefining the Customer

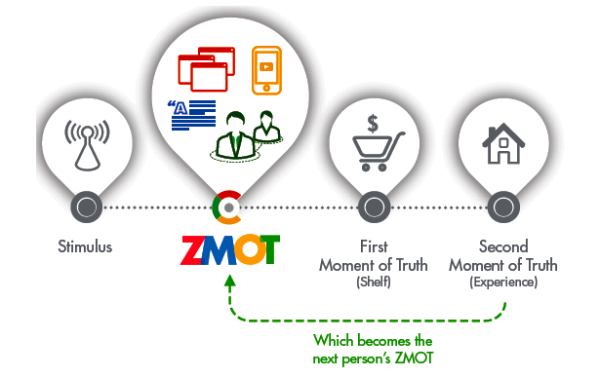

Let’s start with the customer of 2014. In 2011, Google released a study called ZMOT (Zero Moment of Truth) where it detailed the buying behaviors of the online consumer.

In the study, Google found that the traditional methods of marketing no longer held the same influence. Back in the day, marketers researched how audiences responded to new products and services through various methods, some of which included peer groups, test markets, and customer surveys.

The above picture shows the old pattern of buying behavior. Once the stimulus (tv ad, banner ad, or any type of traditional marketing ad) occurs, the customer will confirm or deny the marketing message through their experience.

In contrast, with ZMOT, the customer is in complete control of the entire buying process.

Once the stimulus has been received, the consumer looks online at reviews, user reports, and social media to confirm the stimulus.

At the onset, they control the sales process and no method of coercion can tell them one way or the other if what they hear is true, because they will naturally check on it themselves. To summarize, the consumer isn’t stupid.

If research from 2011 is considered too dated, consider this statistic: 80% of people ignore sponsored ads. Additionally, it’s been proven that banner ads don’t work anymore.

In contrast, organic search results that includes relevant, informative content yields substantially higher returns and is naturally considered more influential in the buying decision. Why? Because it’s real content that pulls from real life in order to solve a real problem.

Despite the popular (and false/pathetic) assumption that corporations use their brands to control our lives, the reality is this: Brands exist to solve to problems. If a brand fails to do that, the consumer puts them out of business by taking their business elsewhere.

Deconstructing Modern Media

Aside from celebrity updates and other gossip media, traditional news outlets like The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Times are seen as top tier journalistic meccas, especially since they moved their platforms to the digital world.

Traditional media networks like CBS, NBC, and ABC have also flocked to the digital landscape, finding their TV ratings plummeting under the weight of 24 hour cable news networks.

Other news outlets like NPR have found a new audience in the millennial generation while The Daily Show and Last Week Tonight do their best to report news under the umbrella of satire.

Within these popular groups, native advertising is considered the necessary evil that sponsors the existence of each medium. This sponsorship is questioned when articles are designed to “blend” with the regular stories within the publication.

In a 2014 study conducted by Matthew Gentzkow and economist Jesse Shapiro showed that publications “with more Republican readers tend to provide more conservative stories and language; papers in more liberal areas lean left in their coverage and story selection.”

The exhaustive study makes the parallel of news to ice cream, in that “Just as ice cream makers give customers the flavors they want, newspapers give their readers the stories and slant they want. It’s a market phenomenon. Ice cream makers strive to maximize ice cream consumption and profits. Papers try to maximize readership and profits. Newspapers are commercial enterprises that respond to economic signals and incentives. Editors, producers and reporters sense what appeals to their readers and try to satisfy these tastes.”

In summary, there is no such thing as “pure” reporting. Regardless of the channel, bias is present – from the battlefield reports in Afghanistan to the mindless rants found on The Daily Show. The viewer goes where they want and in return, are rewarded with the information they want to hear.

Remember when I said the customer is control? Yeah, I do too.

Native Advertising

Enter native advertising. In the aforementioned consequence-free environment where information is passed through an ideological filter at the behest of the publisher and then consumer, native advertising finds itself on a pedestal. Why? If the information within the sponsored ad is incorrect for any reason whatsoever, people get fired. The consequences are real, both for the brand and for the people who created the marketing message.

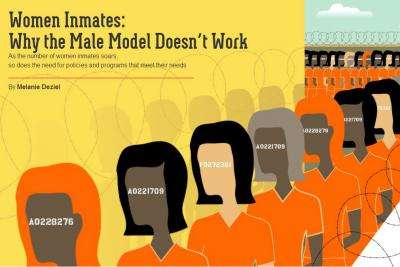

On the flipside, if sponsored content is accurate, helpful, and informative, what’s the issue? Seriously, why the concern? Consider the article used by Oliver in his rant, a New York Times article sponsored by Netflix for the upcoming season of Orange is the New Black.

Yes, he pointed out that the post was sponsored. What he failed to mention was that the article was extremely informative on the topic of the plight of women in the penal system. It contained real information about what is actually happening behind bars. Instead of looking for the sponsored tag on the content, maybe Oliver should have actually read the content.

(If your answer to my question of “why the concern” is that it conflicts the interest of the news organization, please start this article over again.)

Who’s in charge?

Today’s consumer regularly utilizes the omnipresent information god that is the internet and combines it with peer influence through social media. This, joined with direct brand engagement (also through social media), is used to verify that what is being said by brands is either true or not true.

If it’s the latter, then all the resources consumed by the brand and its company in creating the content is a complete waste and could, in the end, be fundamentally detrimental. As a result, jobs are lost, brand influence and growth is stymied, and the problem that the brand is designed to fix exists long enough for a competitor to pick up the slack. In short, the consequences are real and because the consequences are real, the content has to be accurate.

The consequences for native advertising are real and immediate. Not so with traditional journalism, where pundits tailor messages to suit the audience within their fixed demographic, tailoring messages to accomplish their prescribed ideological goal. This makes the native ads more accountable to the consumer which, in a free market, decides if the evil brand/corporation/product is honest.

“It’s generally agreed upon in journalism that there should be a wall separating the editorial and the business side of news,” says Oliver, who uses BuzzFeed-sponsored posts to promote his show. The basic misconception regarding “pure” reporting and “sponsored” reporting is the belief that there is a separation in the first place. All news is business.

Companies need to remember that the consumer is smart. They are able to pick up on sales messages and separate such messages from what they consider to be informative. Brands that work to research, edit, and provide content that serves the consumer with actionable solutions will be accepted (and used) by the reader. Those that don’t, will be penalized by the reader who will spend their time (and money) elsewhere. The consumer is not the perpetual victim of the corporation. The consumer has the power.