Billionaires are increasingly made by intelligent financial schemes of all kinds in the entirely new industry dubbed “asset management.”

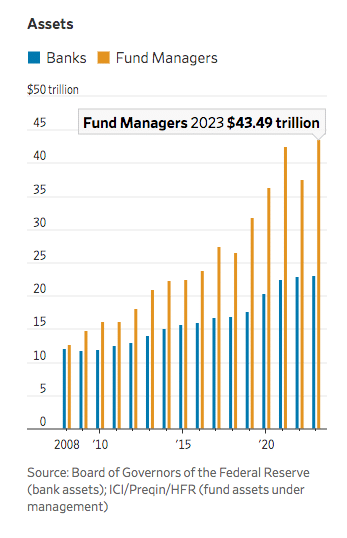

Asset management was once a niche business, but today these investment giants control over $43 trillion in assets – nearly double the $23 trillion held by US banks. How did this transformation occur, allowing asset managers to amass vast wealth while gaining ownership of critical economic assets like housing and infrastructure?

Key Highlights: Billionaire Growth and Asset Management Industry

- Rise of Asset Managers: Asset management has transformed into a trillion-dollar industry, controlling over $43 trillion in assets, nearly double that of US banks.

- Privatization of Infrastructure: Asset managers like Blackstone and Macquarie have capitalized on privatizing critical assets such as housing and infrastructure, positioning them as an “alternative asset class” for high returns.

- Creation of Billionaires: The explosive growth of private equity, real estate, and infrastructure funds has minted more billionaires than any other industry in recent years, with private equity fund managers making up a significant portion of the Forbes 2023 billionaire list.

- Impact on Society: Asset managers have faced criticism for the societal consequences of their ownership, particularly in industries like healthcare and housing, where cost-cutting measures have led to a decline in quality and even fatalities.

- Climate and Privatization: Climate change policies, like the Inflation Reduction Act, are driving further privatization of infrastructure, with asset managers poised to control vast amounts of renewable energy and other critical assets.

The Asset Management Boom Explained

The origins of the modern asset management industry can be traced back to the 1920s stock boom when the first “investment trusts” were created to manage money for wealthy individuals.

However, it wasn’t until recent decades that asset managers transitioned from being a small niche business to becoming an economic force owning companies, real estate, and infrastructure worldwide.

Several key factors drove this explosion in the 1970s-1980s:

- New pensions legislation expanded the pool of investment capital.

- A trend towards outsourcing led institutions to hire asset managers rather than hiring their own professionals.

- Asset managers started offering lower-fee index funds to attract retail investors.

- They began investing in physical assets like housing and infrastructure aside from just stocks/bonds.

“What we do is behind the scenes. Nobody knows we’re there…”, said Bruce Flatt, CEO of Brookfield Asset Management in a 2018 interview underlining how these firms operate in the shadows while exerting growing control.

The privatization wave in the 1980s-90s was a massive opportunity for asset managers to buy up former government-owned housing, utilities, airports, and other infrastructure cheaply. Firms like Blackstone, founded by Steven Schwartzman, and Australia’s Macquarie became pioneers in treating these physical assets as an “alternative asset class” to market to investors seeking higher returns.

Today the largest asset managers like BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, and Fidelity control over $26 trillion in assets, equivalent to the entire US GDP. However, private equity and debt funds like Blackstone, KKR, and Apollo have seen their assets double to $6 trillion in just four years – far outpacing public funds.

Building Financial Supermarkets to Entire Retail Investors

Traditional asset managers who dominated public investing are rapidly building out private equity, debt, real estate, and other alternative investment companies to become “financial supermarkets.” The lines are becoming blurred and more assets and power are getting concentrated under the same roof.

For example, BlackRock struck a $12.5 billion deal to acquire alternative asset manager Global Infrastructure Partners. If approved, this record acquisition will mint six new billionaires from GIP’s founding partners.

Other asset managers are developing new funds and products to sell alternative investments directly to individuals and retail investors – a market previously limited to institutional capital or high-net-worth individuals.

This raises concerns about proper risk disclosures for unsophisticated investors who are buying into complex and illiquid investments.

“We’re moving into a gray area as asset-management businesses move into different silos of financial services”, said Tyler Cloherty from Deloitte. “The big question I’m getting is ‘What do we do around getting alternatives to retail clients?’ There’s a lot of complexity there.”

Billionaire Wealth from Alternative Investments

The explosive growth of private equity, real estate, infrastructure, and credit funds has minted more new billionaires than any other industry in recent years.

According to Forbes, private equity fund managers took 41 spots on the 2023 US billionaire rankings. This represents 5.5% of the total number of billionaires on the list – a percentage that has nearly doubled since a decade ago.

The founders of alternative asset management giants like Blackstone, Apollo, and KKR are projecting that their firms’ assets under management will double again in just a few years by pushing further into individual investor markets. This trajectory would create even more billionaires.

Critics question if the rising complexity and scale of these organizations are creating risks that markets have never encountered.

The Asset Management Industry Is Literally Killing People

While promising higher returns, asset managers have faced criticism over the societal impact of their ownership of housing, utilities, and infrastructure that were historically owned by governments or regulated utilities.

A 2021 study in the National Bureau of Economic Research’s newsletter The Digest found that patients at nursing homes owned by asset managers had a 10% higher probability of death compared to other for-profit facilities. “Some 20,150 Americans lost their lives between 2004 and 2016 specifically due to asset-manager ownership,” the researchers concluded about the consequences of the cost-cutting measures and pricing decisions adopted by these companies to maximize their profits.

Beyond higher costs and deteriorating quality for captive customers, there are also massive systemic risks as a few giants concentrate ownership across large swaths of the economy.

This securitization of critical assets and the disconnection between the interests of asset managers and the communities their businesses serve could have severe consequences if economic turmoil disrupts the funds. If just one of these titans falls, the entire global economy will likely crumble alongside it.

Climate Crisis is Accelerating Privatization

Governments have kept pushing for infrastructure privatization, often subsidizing private capital, as policies to address climate change rely on quickly building new renewable energy projects, transmission lines, and other related assets.

President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act provided billions in tax credits to catalyze private investment in climate infrastructure, mirroring similar plans proposed by the UK Labour Party to have asset managers finance the energy transition.

Sure enough, giants like Blackrock and Brookfield are raising new funds to control clean energy assets globally. Blackrock’s $673 million Climate Finance Partnership pools money from development banks and charitable groups to prioritize their climate bets, illustrating the model of privatizing risks and profits going forward.

Also read: Private IPOs: Will the Elite’s New Playground Leave Everyday Investors in the Dust?

With asset managers increasingly and rapidly positioning their businesses to scale up their ownership of housing, transportation, energy, and other critical assets through climate policies, the concentration of control – and implications for costs, quality of life, and financial stability – could reach new heights if left unchecked.

Lawmakers have started proposing regulatory measures like updated disclosure requirements for private fund fee structures.

However, critics argue that much stronger oversight and public interest protections are required as asset management billionaires increasingly govern critical infrastructure with maximizing profits being their sole mandate.