More than $100 billion in commercial real estate loans on US office buildings will mature over 2024, presenting owners with a formidable refinancing challenge. With interest rates significantly higher compared to when most of these loans originated in the last decade, billions in losses appear inevitable amid depressed property valuations.

Pain Set to Impact a Broad Cross-Section

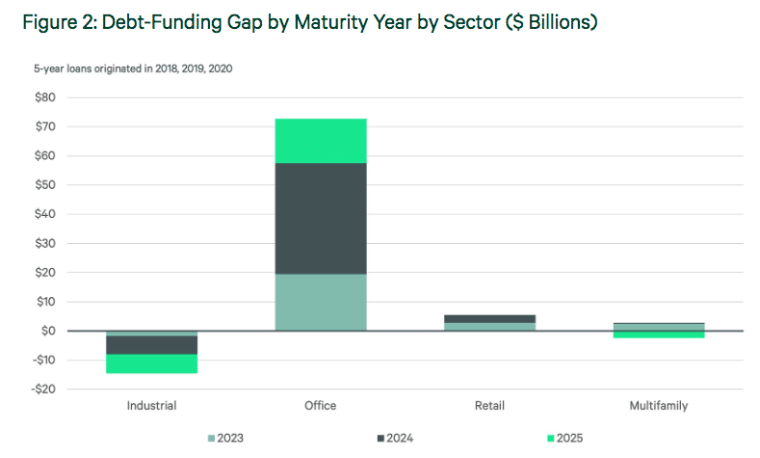

The sheer volume of 2024 maturities suggests that some degree of financial pain will likely sweep across many institutional and private owners. Data from the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) reveals that roughly $117 billion worth of office mortgages expire next year and will either have to be repaid or refinanced.

Owners leveraged office portfolios near peak valuations, expecting that rents would continue rising. However, remote work disruptions rapidly changed things in the office landscape, leaving owners squeezed between plummeting demand and unaffordable refinancing rates that doubled over the last decade.

Also read: Best Real Estate CRM Software: Top 10 for 2023

“We’re seeing deals where even sophisticated borrowers are calling it a day and asking their lenders whether they would like to take the keys”, commented John Duncan from the law firm Polsinelli, which specializes in the real estate market.

With balloon payments coming due, negotiating loan extensions or discounted payoffs with lenders offers some recourse. However, with rent rolls depressed indefinitely, injecting extra equity may be owners’ only option to hold assets and avoid foreclosure. Many will simply cut losses.

Office building loans are typically interest-only instruments that demand minimum installments from owners. However, once the loan is due, the investor – institutional or individual – has to either pay the full amount of the loan’s principal or transfer the property to the lender.

At a point when property valuations have been severely depressed by the latest interest rate hikes, financial institutions may find themselves struggling to unload some of these properties and could face billions of dollars in losses from loans that did not perform as expected.

Billions in Losses Anticipated Across the Lending Sphere

Banks face less immediate risks than alternative lenders like private equity firms or hedge funds. Regulated institutions hold almost 70% of soon-to-mature office loans and can negotiate long-term workout agreements. Still, soured office exposure might result in short-term losses that can hit their financial performance for a while.

Healthy developers with low-leverage buildings can probably manage balloon payments, but too much risky lending before the pandemic has already weakened safety nets. Some serious consequences have already been seen. A key example is the bankruptcy of the Austrian real estate company Signa, which went into administration and had to sell its share in the famous New York Chrysler building to generate funds.

Less diversified owners utilizing higher-risk commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) for financing remain the most exposed. Industry data suggests a quarter trillion worth of these CMBS contracts float through global financial systems. This presents significant systemic risks if mass office defaults spark contagion.

Some Studies Point to Regional Bank Vulnerabilities

While diversified global banks seem insulated, undisclosed regional lender exposure to troubled office assets is a worrisome reality for certain analysts. One academic study indicates that 40% of all office loans held by US banks are currently underwater.

Authors noted that, while modest delinquency levels have been reported thus far, the numbers likely lag real-time troubles. Meanwhile, with hundreds of regional banks mired in office markets like New York and San Francisco, paper losses could rapidly transform into tangible balance sheet holes.

How many overleveraged owners without Signa’s scale may be facing similar scenarios? Analysts expect that 2024 will offer further clarity regarding the true situation of the sector.

Owners Overleveraged Properties During the Era of Easy Money

When examining the roots of today’s dilemmas, the numbers reveal excess permeated pre-2020 commercial real estate lending. Consider Manhattan’s prestigious Seagram Building along Park Avenue.

When refinancing its $760 million mortgage in 2013, optimistic lenders projected 30% more annual rental income in the future than the tower ever generated. By 2018, the property already missed those lofty targets by 15%.

That pattern characterized cheap debt flooding to office markets for over a decade. When the pandemic hit and buildings were emptied, inflated underwriting collided with reality. Now, despite recovering occupancy rates, the Seagram Building’s 2022 income remains almost 50% below its 2013 financial model projections.

Leverage metrics illustrate how quickly scenarios can destabilize the market. Put simply, some buildings now owe much more than they are worth.

Market Analysis Shines Light on Specific Geographies That May Be Most Exposed

The CBRE Group recently developed a proprietary distress benchmarking model analyzing metro office markets. The model incorporates local factors like demand changes, cap rates, and asset valuations to quantify distress levels relative to prior cycles.

Their results reveal that current conditions equal nearly 80% of what markets weathered during 2009’s Great Financial Crisis (GFC), with numbers still deteriorating in 2023. Further context shows that gateway cities like Manhattan and San Francisco are suffering disproportionately from shifts in office usage.

Nonetheless, investors’ appetite for premier buildings in top-tier markets could help cushion downside risks. For example, one report suggests that demand from Asia and the Middle East might stabilize troubled West Coast markets as overseas capital may view a correction cycle optimistically.

US Economy & Lenders Face Reality Check

In essence, years of loose lending environments and Obama-era economic policy created abundant capital chasing limited prime property assets. Risk metrics stretched thin as investors gambled that a decade of steady office rental growth would continue unabated. However, business model disruptions sparked by COVID shutdowns threw all of these overly optimistic assumptions out of the window.

Now, the fallout settles across financial markets and boardrooms alike. Lenders face writedowns, developers scrambling for refinancing teeter at default’s edge, and bankers eye exposure reports warily. Ultimately, the reckoning will separate disciplined capital allocators from reactive speculators.

Of course, opportunities would emerge for cash-rich groups that may be ready to buy discounted buildings or stabilize struggling borrowers with fresh equity. Still, the breadth of overleveraged office portfolios ensures no swift panacea for projected funding gaps.

Thus 2024 shapes up to be the first real test for the office segment of CRE. With buildings flooded by easy money last decade in desperate need of refinancing, reality will finally scrutinize those carrying stretched debt burdens.