“We should have a higher overall cancel rate.”

– Reed Hastings, Co-Founder & CEO Netflix

June 2017. While his company is enjoying unparalleled subscriber success, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings is worried that his widely loved streaming service is having too many hit shows. “It’s a sign we’re not trying enough crazy things. We should take more risks.”

Was Hastings trying to hedge his company’s position towards investors in the sight of more cancellations? That’s a way of looking at it. The other way is that he’s willing to sacrifice a fraction of today’s profits to ensure Netflix’s growth tomorrow.

Or should we call it survival? After all, Netflix’ rise coincided with the fall of Blockbuster as the latter neglected the future to make more money in the present. “Why would we care about you mailing DVDs if we’re making billions of dollars a year with our physical stores,” is what I imagine Blockbuster CEO John Antioco replied to Hastings when he proposed to join forces in 2000. Blockbuster declared for bankruptcy in 2010.

Hastings could’ve also gotten his inspiration from Netflix’ current rival, Amazon and its charismatic founder Jeff Bezos. Bezos, soon-to-be wealthiest man in the world, doesn’t make a secret of what his secret sauce is. “Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day.”

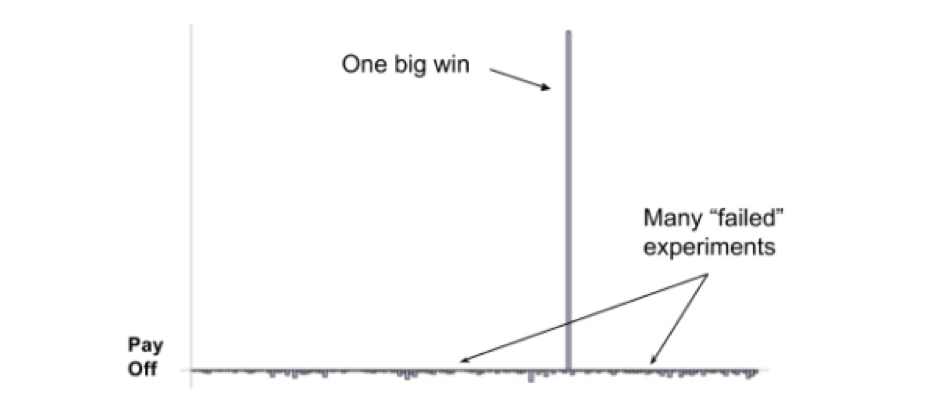

Bezos likes to compare business to baseball. If you swing for the fences, you’re going to strike out a lot, but you’ll also hit a couple of home runs. The difference between business and baseball however, is that in baseball the outcome is at most four runs – no matter how well you hit the ball. In business, you can get up to 1,000 runs and more.

Image Credit: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

So even if you miss nine times out of ten, the massive potential return justifies being bold. If you want to win, you need to experiment. No need to look further than Amazon Web Services (AWS) to understand that Bezos is right on the money. Starting off as an experiment totally unrelated to Amazon’s core e-commerce business, AWS became the fastest growing B2B company in history and has given Amazon the kind of digital infrastructure no other e-commerce business can ever catch up with. The same can be said about Amazon Prime, Echo and Kindle – all multi-billion dollar experiments that paid off.

Are you learning as fast as the world is changing?

Startups often pride themselves on out-hustling their competition. I too wake up every morning with the mindset that nothing is off-limits if you put in the work, but just putting your muscles to work isn’t going to cut it. More than ever, the one question leadership should be able to answer is: how do we learn as fast as the world is changing? Rather than ‘what’ you think, the crucial skill today is ‘how’ you think.

Netflix doesn’t care as much as having hit shows today as it does about having hit shows tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. They want to able to out-think the competition, to develop a privileged point of view of what the future will look like and get there before anyone else does.

Their vehicle to get there? Experimentation. The same vehicle Amazon, Facebook, Google, Uber and many others are riding. There’s a reason experiment-fuelled companies have been emerging as the best of the class in short span of time: they’ve developed better mechanisms to grasp reality and internalize the learnings into their strategies. The closer to reality you stand, the better decisions you make.

Experimentation used to be considered something a company could do on the side, while the other 99% could focus on the ‘core business’. Today it’s a prerequisite to play the game and the players compete on the quality, volume and pace of experimentation.

Experiment-driven marketing

Growth hacking is nothing but figuring out the fastest ways for growth through rapid experimentation across marketing channels.

Netflix making crazy shows to see how their subscribers react to it and gauge their changing consumer preferences is no different from me throwing up a landing page for a crazy new product feature. As a growth marketer, I too am looking to learn more about reality by throwing something at it and see how it reacts. Is the marketing message I’m sending viable, does it resonate with target audience and does it have ROI potential for the business?

Once I know, I can use that learning – whatever it might be – to revisit my ideas or generate new ones to then design new experiments to test those ideas. Slowly but surely I’ll iterate my way to the formula that determines growth for my business.

“What’s the number one growth hack for my company?”

The most frequently asked question prospects ask me in sales meetings is also the one I love most.

As soon as it pops, a trace of a smile plays across my lips.

It’s the perfect opportunity for me take control of the conversation and enlighten the prospect on what makes our agency different from others.

“Science.”

They look at me with big eyes.

They expected a magic formula, a silver bullet, a stroke of genius.

I give them a methodology, a process.

And explain why they’ve been reading too many ‘how to increase your traffic with 350% in two weeks’ – blog posts.

“I am the wisest man alive. For I know one thing and that is that I know nothing.”

This quote is by the famous Greek philosopher Socrates and I live it religiously as a growth marketer.

When I get into a sales meeting with a prospect, I know nothing.

I don’t know their product, I don’t know their audience and I don’t know their business model.

That may sound like a disadvantage, but it isn’t.

It means I’m 100% free of assumptions: things I think I know but don’t actually have proof for. Every such an assumption is essentially a risk to your business because you don’t know if it aligns with reality or not. And boy do entrepreneurs have a knack for thinking they have their companies figured out. Their business models are swamped with risks disguised as assumptions. The worst kind of risks: risks of which you don’t know that they’re risks.

As an outsider, I am in a better position to assess the assumptions that lay at the grounds of the business and turn them into experiments to find out whether they’re true or not. If an experiment proves an assumption to be truthful, I now have data to back it up and have stripped the business model of a risk. If an assumption proves to be wrong, I’ll have learned something new – putting me in the position to turn a risk into an asset.

Whichever one of the two it is – right or wrong – strategic decisions for growth today can be made from evidence and not gut feeling. Marketing used to be about big bombastic campaigns that would take months and millions of dollars to set up without a valid way to track actual ROI. Those days are over. With the tools and tracking possibilities we have at our disposal today, there’s no more excuse to make decisions purely based on gut feeling. Let alone complain about the outcomes after. You can know the exact return of each marketing dollar you spend.

A quest for truth

Marketing is about understanding and influencing customers behaviours. We aim to make people react to stimuli in predictable ways. For every action, there is a reaction and we want to be able to anticipate those reactions as much as possible.

That makes marketing a never-ending quest for truth. Never-ending because the idea of truth itself is an illusion. As human beings, there’s only so much we can grasp from reality. It is too vast and complex for our brains to fully make sense of, and changes at unprecedented speeds. Experiments are our gateway to reality. One experiment will tell you which subject line gets more opens, which image converts better and which copy gets clicked more. A series of experiments will gradually make you understand what your customers need, what moves them, where they hang out, how they like to be talked about. And how all of that can come together in a brand and marketing strategy.

The pitch I make to prospects pretty much comes down to this. When it doesn’t do the trick, I give them the link to Ladder.io’s Playbook with 849 growth tactics and propose they guess which ones might work for them instead of actively finding out what will work.

What we call a ‘growth hack’ is the result of a thorough understanding of your target audience and its relation to your business. You find one by slowly making sense of the complex reality that is a business.

Dropbox’s growth hack wasn’t the referral program

From September 2008 to January 2010, Dropbox grew from 100,000 to 4,000,000 users.

I’m guessing you heard this story over and over again. What I’m not sure about is whether they’ve told it to you the right way.

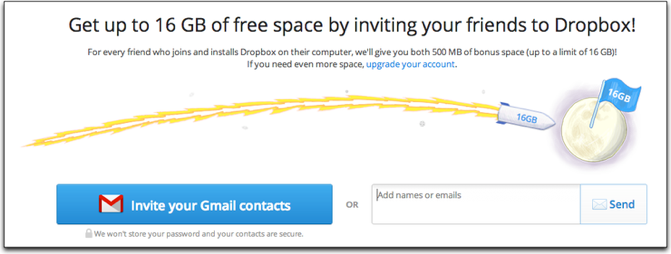

Sean Ellis drove virality by inventing the modern referral program: users who got their friends to sign up for Dropbox received 500MB of extra storage, an enormity at the time.

Businesses from industries all over the world were quick to ‘steal’ the referral program, only to find out it wasn’t performing for them as it was for Dropbox.

They copied the wrong strategy.

Dropbox’s success isn’t built on the referral program, it’s built on the process that gave rise to their referral program: experimentation.

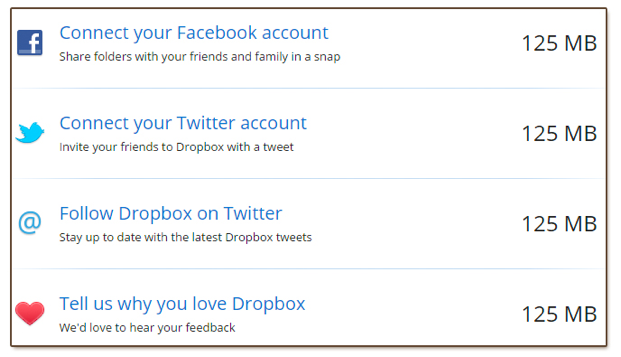

Before doubling-down on the referral program, Dropbox conducted small experiments to find out how far users were willing to go for free storage space.

Experiments like these taught Dropbox users were willing to perform certain actions to gain extra storage. They went from connecting social media accounts to inviting friends and eventually mass-inviting friends through a clever integration with Gmail.

They didn’t discover the referral program as a growth hack overnight. It was the logical consequence of an ongoing loop of small-scale experiments. Experiments that gradually revealed the referral program as a major growth lever for Dropbox. First they discovered they were getting a lot of referral signups for enthusiastic early adopter users by looking at the data, then they ran experiments to find out whether people would perform certain actions to get free storage – the logical consequence was the referral program

The simple reason this referral program doesn’t work for you the same way it works for Dropbox is that your customers aren’t the same as Dropbox’s.

It sounds obvious and yet every day again people ask me if I can give them plug-and-play growth hacks for their businesses.

This obsession with tactics over process is the number one thing people get wrong about growth hacking. Your growth hack isn’t someone else’s.

To quote growth hacking godfather Sean Ellis:

“Sustainable growth comes from understanding best customers and figuring out how to find and acquire more of them.”

– Sean Ellis, Growth Hacking Godfather

Similarly to how Dropbox learned its users would be willing to refer friends to get more storage, Twitter found out all of its active users followed at least thirty people and Airbnb found out its target audience was looking for vacation rentals on Craigslist.

Both then turned those learnings into effective tactics. Twitter started showing users interesting people to follow in the signup process to boost activation. Airbnb built an integration to cross-post listings on Craigslist to drive awareness.

The rest, as they say, is history.

These examples come to show that growth comes from relentlessly pursuing the truth about your customers through an iterative process of experimentation: test, measure results, internalize learnings, rinse and repeat.

Embrace failure as a tool to make better decisions

I can’t tell you how many entrepreneurs I meet that hold the flag of creativity and innovation up high, yet fail to act on it because of fear of mistake and disappointment. They’re afraid to be wrong. Which in turn is why they lack both innovation and creativity and get outmanoeuvred by competitors who are willing to experiment and fail.

Rather than being afraid of being wrong, you should strive to be less wrong. Experiments and failure are inherently connected with one another. No matter how well-designed, 9 out of 10 experiments will fail, for the simple reason that as human beings we’re way worse at understanding reality than we think we are. Which is exactly why we need failure: it teaches us reality.

“I haven’t failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

– Thomas Edison

Failure as a teacher is a liberating idea, because it implies you can’t lose. Losing would be not knowing, staying stuck in the dark guessing why your traffic isn’t converting.

What most companies don’t get is that failure is a feature of learning, not a bug. If you’re not prepared to fail, you’re not prepared to learn. In fact, most breakthrough ideas are hidden within ‘failed’ experiments.

There is no such thing as failed experiments – only unexpected outcomes.

If the demographic you expected to click isn’t clicking that means you need to adjust your message. Or adjust your focus to target the demographic that is clicking, often with substantial implications for your initial value proposition altogether.

Consider the case of ‘Circle Of Friends’, a sort of Facebook Groups before there were Facebook Groups: people could organise themselves in self-managing communities. KPIs for activation and retention weren’t met, except with one target audience: moms. Moms were using it intensively to connect with one another and share best practices on parenting. The then startup realigned its value proposition, rebranded to ‘Circle Of Moms’ and was acquired by PopSugar four years later.

Reality is too complex for us humans to predict. Experiments are what enables us to test our ideas in reality. Failure is reality’s way of getting back to us and show us what’s real and what’s not. Whatever happens, there’s always a learning you can take with you.

The Minimum Viable Experiment

If you’re going to double the number of experiments you do per year, you’re going to double your inventiveness.

– Jeff Bezos

The best part about this Jeff Bezos quote is that it’s actually inaccurate.

If you double the number of experiments you do per year, you’re going to more than double your inventiveness.

Think about it. Every experiment widen and deepens you knowledge. New knowledge allows for better experiments, better experiments allow for richer insights and richer insights again allow for better experiments. Rather than double, your inventiveness will grow exponentially. This is the idea of the compound effect.

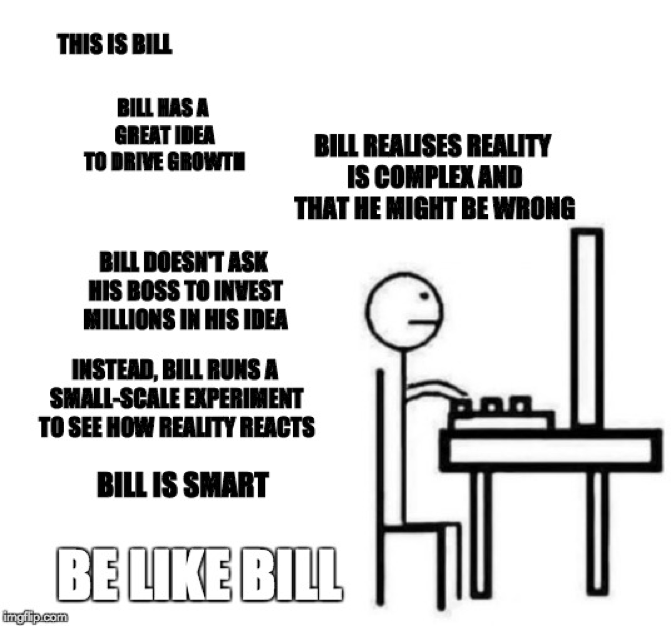

Speed of execution is key here. The goal of experimentation is to learn and stack up knowledge quickly, not to be perfect and look pretty. If you have a new idea to acquire customers, you should test it in the real world as quickly as possible before designing a whole strategy around it.

This also has to do with resources: why spend huge amounts of time and money on Instagram ads or a new product feature if you have no clue if it will appeal to your target audience? As soon as an idea hits you, you find a way to put it out in the real world as a fast as possible and see what happens. You test with a small target audience to avoid a big budget gamble.

It doesn’t have to be good, it has to be good enough to validate or dismiss your assumption underlying the idea: a Minimum Viable Experiment.

I can hear you thinking already: “yeah yeah, build an MVP before going all-in.” But do you stick to that idea through thick and thin?

My experience is that aggressive growth KPIs often drive teams to forget about the minimum part of their MVE. Apart from the learning, they also strive to drive KPIs and, without realising it, end up with blown-up failed experiments, expensive in terms of budget and time.

Take the example of a startup that believed introducing a subscription model would be huge growth opportunity. Instead of testing that assumption in an MVE, they went on to change their payment system and onboarded existing users in the subscription model. To then, after about two months come to the conclusion a subscription model didn’t appeal to their target audience at all. They could have easily tested this without risk by putting up a landing page for a subscription signup, driving traffic to it and compare conversion on it against the current pricing model.

Fake it if you have to. One hour, a computer and an internet connection are sufficient to put together a mockup of two, a landing page and a Facebook Ad to drive traffic and see how your idea, be it marketing or product, stands the test of reality. If you can’t think of a way to fake a product experience in order to get your hands to validating data, you’re not trying hard enough.

Growth Hacking, demystified

To its core, growth hacking is an amazingly simple concept.

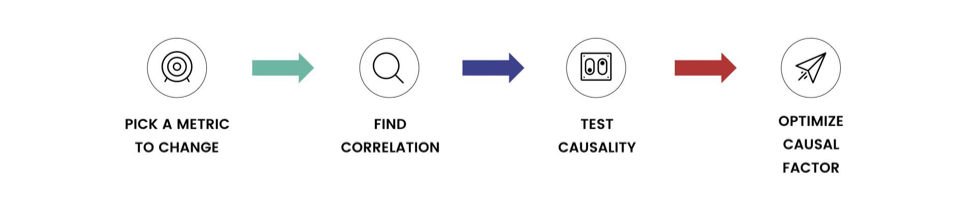

First, you pick a metric that you would like to see go up or down. This can be number of signups, number of returning users, CTR on Facebook Ads, email opens or the number of coffees you drink per day.

Then, you look for other factors you believe influence that particular metric. You may believe signups go up if you remove a step from the signup process, think gamification will spike retention, assume emojis in copy will make people click more, be convinced emails sent in the morning will get opened more and trust you’ll drink less coffee if you sleep one hour a night more. Ideally, you base this influencing relationship on data – data you already have or data you have seen elsewhere. Something that tells you there is a correlation between the two factors. If you don’t have any data, because your idea is particularly new and/or you’re just starting out, you go by gut feeling. You may have found research that sleeping more reduces coffee consumption or you just believe it to be true.

Once you’ve identified the two factors that are correlated – the one you want to change and the one you think will change along with it – you’re going to figure out a way – an experiment – to test if that correlational relationship is also a causal one: does the one factor’s change determines the other factor’s change? Translated: if I send my emails in the morning and the open rate goes up, is it because I sent them in the morning? To know this for sure, you can for example send the exact same email with the exact same subject line to half of your email list in the morning and the other one in the evening. That way you exclude the possibility of other factors being the causal drivers of the metric change.

When you’ve found causality between two factors, backed up by nice and unambiguous data with every other possibility excluded – you can optimize the causal factor to drive the metric you picked in the very begin up to the point where you want it to be.

Your Most Powerful Growth Hack: The Scientific Process

Time to get our hands dirty and practice some science.

You don’t need to be Einstein to do this. Science is about pursuing curiosity, embracing ignorance and relentlessly bridging the gap between the two.

The scientific process will remove the guesswork from your marketing and turn your company’s growth into something scalable, predictable and repeatable.

It goes something like this:

- Set goals

- Ideate on how to reach goals

- Design experiments to test ideas

- Execute experiments to see how reality reacts

- Study data & document relentlessly

- Rinse and repeat

Step 1: Set Goals

Always start with the end in mind.

Are you looking to drive more traffic to your website, reactivate idle users or increase revenue from upselling?

Simply ‘drive more traffic’ isn’t going to cut it. To design effective experiments, you want to break down your objective in more manageable parts following the SMART criteria: Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic and Time-related.

Let’s assume you run an e-commerce business with 14,000 monthly unique website visitors and an average spend of $7.3, resulting in $1,226,400 annual revenue. To get to $2,000,000 by the end of next year, you’ll need to either grow your website traffic to 22,832 monthly unique visitors or increase average spend per visitor to $11.7.

Your goal could look like this:

We want to increase website traffic to 23,000 monthly unique visitors within 90 days — weekly growth rate of 13%.

Here’s how that aligns with the S.M.A.R.T. dimensions.

- Specific: increase website to 23,000 monthly unique website visitors

- Measurable: 13% per week

- Assignable: the marketing team

- Realistic: Up to you to decide what is ‘realistic’.

- Time-related: Good goals are set between 30 and 90 days.

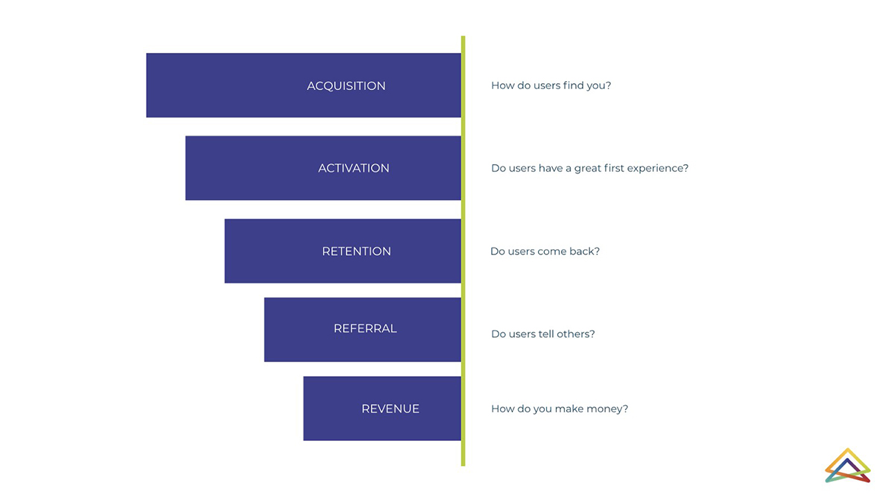

Base your objectives on the pirate funnel to align your experiments to stages in the customer journey.

Driving website traffic is just one example of how you could trigger growth. Every stage of the pirate funnel offers opportunities in this respect. Be smart about which stage of the funnel you’re going to grow first: it doesn’t make a lot of sense to double traffic to your webshop if 95% of your visitors leave without spending.

Step 2: Ideate on how to reach goals

After the ‘what’ comes the ‘how’.

This is where you come up with ideas to reach your objectives. In this case: to increase traffic with 13% in a week.

Try to find to find a balance between ideas you base off data from past experiments and totally new experiments. That way you’ll be able to improve existing tactics as well as maximise your odds to discover new ones.

Let’s say past experiments have proven Instagram ads to be an effective traffic driver. You can try to improve those past experiments in terms of media, copy or targeting to gain a bigger increase in traffic.

Another idea is to start following influencers on Pinterest because you’ve seen competitors doing it and want to find out if it would work for you too.

More ideas:

- team up with other e-commerce businesses for a big giveaway and share email lists and Facebook Audiences to cross-promote it

- create a chatbot that helps people choosing the best gifts for their mother, father, sibling, friend etc. — write a blog post about it, share on social/in relevant communities and post on Product Hunt

- start shipping stickers with orders to increase offline exposure

Come up with as many ideas as possible, then select the ones you want to focus on in the upcoming weeks and put the rest in your backlog to revisit later.

Step 3: Design experiments to test ideas

Turn ideas into experiments by identifying:

- the hypothesis to validate

- the variable to test

- the metric to measure

- the criteria to base success off

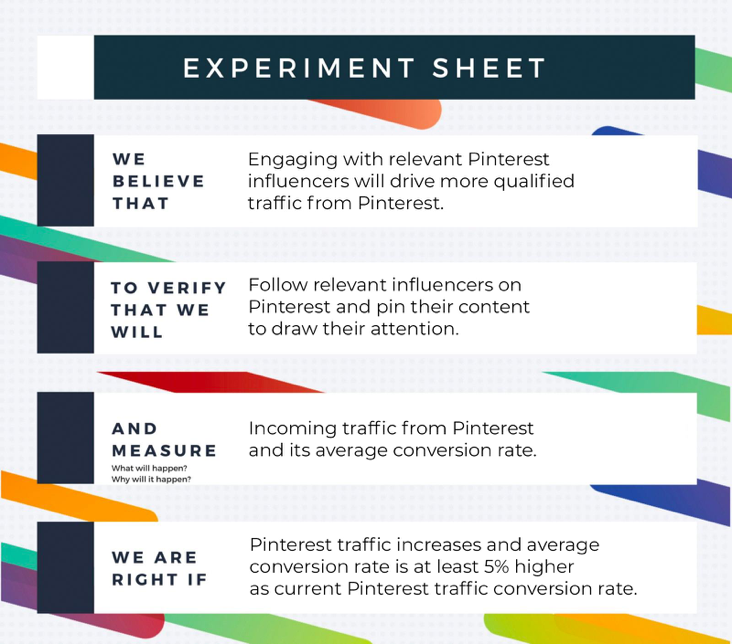

For the Pinterest-idea, that would look something like this:

As soon as I’ve confirmed that following influencers on Pinterest works, I can run further tests to determine the characteristics of the influencers most likely to follow me back and pin my products. The more experiments I run, the more I’ll get to know Pinterest as a social platform and the more I’ll be able to eventually turn it into a traffic machine.

Stay true to the idea of the Minimum Viable Experiment.

- Don’t waste time on perfecting copy or design. Implement whatever is need to validate/dismiss your hypothesis.

- Don’t burn your monthly budget on one ad campaign. Start with a fraction and scale up as it gains traction.

- Don’t make ten changes at once: test one element at a time to learn its relative weight in relation to the other elements.

- Don’t argue about which ad looks the best: A/B test all of them in the market and the best one will automatically emerge.

Step 4: Execute experiments to see how reality reacts

Time to unleash your experiments into the world.

Work hard, but smart. Use tools to facilitate and automate non-creative work.

You can draw inspiration from Google’s design sprints to schedule experiments, manage time and assign tasks.

Step 5: Study data & document relentlessly

The most important stage of the process is also the most overlooked one.

About every marketing agency these days claims to be ‘data-driven’ but few of them really are.

The whole point of the scientific process is to discover new knowledge and internalize it to gain power over your reality. There’s no sense in running experiments if that new knowledge is then ignored, overlooked and not captured.

Take the time to look at the results of experiments and try to understand the surrounding ‘why’ by combining quantitative with qualitative data.

Here are some guiding questions:

- What were the results of the experiment?

- How valid was the initial hypothesis?

- Why are the results what they are? Try to understand the whole story, not just the occurrence.

- Are there ways to segment or combine data to reveal new insights?

Remember: breakthrough insights are hidden within ‘failed’ experiments.

Document your experiments relentlessly. As experiments are all about learning and the most powerful learnings are often hidden within the failed ones, it is crucial that you keep track of what you have been doing and internalize learnings to avoid spending time on finding out things you already know.

Step 6: Rinse and repeat

Congratulations, you’re smarter now. Now use that to become even smarter.

Align goals, scale successful experiments, adjust failed experiments, come up with new ideas, design better experiments and harvest new learnings.

To then do it all over again.

There’s always more things to test, more experiments to run, more knowledge to gain. You can never win the game but the more you play, the better you’ll get.

Looking to fuel your experiment machine?

On June 7th of this year, my agency The Growth Revolution will be setting new standards for conferences on growth in Europe with The Growth Conference in Antwerp, Belgium.

Read more: