What is it like starting and growing a business in a time of technological disruption, changing social conditions, and shifting economic priorities? Exciting, vital, dynamic, and thrilling, in one perspective. Others take a bleaker view of the prospect.

Some companies prosper and thrive in uncertain conditions, while others cannot.

Rapid change brings increased risk, and also bigger payouts. Speed becomes the new currency for capitalizing on the opportunities that result from disruption. Risk becomes more and more baked into the calculus of opportunity.

The age of disruption is also the age of experimentation. Experiments are risky but they can yield entirely new formulas and models.

Strategy still matters but adaptability and responsiveness come first. It was under conditions like these that General Eisenhower said, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” While plans are too rigid for the multi-variate conditions of this environment, planning primes project leaders to take action quickly when conditions change.

In the past, finding a winning model usually translated into long-term prospects and growth, as businesses charted a fairly predictable course from seed to maturation, and exited the market tidily after a long and prosperous course. This business model was built around stability, tradition, and longevity—which also reflected the markets.

Quality control, economies of scale and mass production typified the close of the industrial era, set into motion in the early 19th century.

This is no longer a given. For example, the average tenure of companies on the S&P 500 in 1958 was 61 years. That decreased to 25 years in 1980 and is just 18 years now, a number forecasted to dwindle to 14 years in 2026.

What does this decreased lifespan portend for business?

Such a shortened lifespan points to the changing nature of business itself. The business cycle has shortened, and the accelerating pace of innovation—and competition—is disrupting the old linear model of business and replacing it with new, dynamic model.

Today, agility rather than longevity is winning. In fact, characteristics that once contributed to corporate longevity and denoted a healthy culture, such as the ability to ‘stay the course,’ now could utterly sink a company. Old-world virtues slow down learning, iteration, decision-making and, ultimately, creative action.

Consider the five stages of a business lifespan:

- Seed and development—ideation, feasibility and fundraising

- Startup—product development, market testing and iteration

- Growth and Establishment—improved cash flow, established customer base and brand identity

- Expansion—expanded offerings and new markets

- Maturity and exit—every idea or product reaches a crisis stage, a point where improvement plateaus, expansion is no longer possible, and profits reach a ceiling.

Now there needs to be added a sixth stage:

- Rebirth or return—in this stage, a company starts over again, reinvesting its resources in new innovation.

A business today doesn’t experience these stages progressively, but dynamically. A healthy company might be investing its energy in several stages, for example, exiting from an unproductive segment and iterating a product for new markets, while raising funds and exploring new innovations.

The Living Dead

What happens to companies that don’t exit but also aren’t able to make the leap to a new innovation?

Companies that outlive this stage without an exit or rebirth become a drain on the economy, consuming resources that would be better utilized by innovators at the beginning of the cycle. They may even have an established customer base and brand identity but still be unable to contribute meaningfully. These companies, the non-producers, place a drag on the larger economic cycle upon which all businesses and consumers mutually depend.

We can see this today with zombie companies, defined as businesses that do not make enough earnings after taxes to cover their interest payments. Research by Chris Watling at London Longview Economics estimates that at least 12% of all American companies are zombies. These companies are at least ten years old (to exclude young companies in their acceleration phase) and have failed to keep up with their interest payments for at least 3 years.

Low interest rates kept some of these zombies alive during the era of central bank monetary intervention, but now that interest rates are rising, they might rely on corporate tax cuts continue to subsidize their non-productivity.

The promise of tax reform for spurring real economic growth will depend on whether such companies that are no longer innovating will be allowed to benefit. Reduced taxes can spur new innovation and rebirth, or merely keep zombies on life support (as low interest rates have done).

Meaningful tax reform should exempt companies that aren’t innovating. Just like companies, the larger economy needs to jump to a new innovation cycle. Technologies like AI and machine learning are promising productivity gains and an economic boost. But if all they do is give a second life to companies and industries that aren’t innovating, true growth will stall, and possibly drive the majority of the world into a dark age.

Healthy, productive, innovation creates new wealth and allows many new ideas to nest within it, a vibrant ecosystem.

But what does healthy innovation look like?

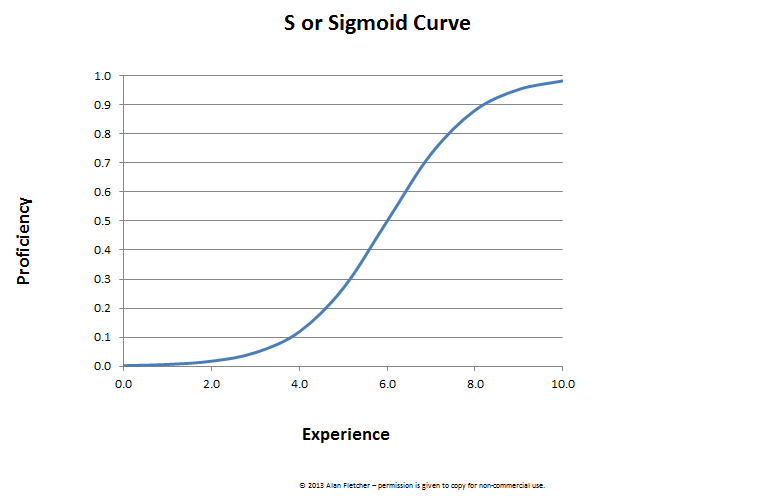

S-Shaped Growth Curve

The Sigmoid growth curve is a common mathematical form found in many biological ad statistical systems. For example, the S-curve is found in the pattern of population growth that describes how a population of organisms react to a new environment.

The population density of an organism will start out at a steady rate, then accelerates slowly before hitting a stage of exponential growth. Eventually, growth stalls then declines in a negative acceleration as it encounters resistance or ‘friction’ in the form of environmental limits. The point of stabilization, or zero growth, is termed ‘saturation value’.

While the S-curve is used to describe behaviors from the spread of bacteria to the formation of neurons, it also can map the trajectory of many different processes and events—supply chains, technological innovation and adoption, business growth and innovation, etc. Demand follows an S-curve, technological development follows an S-curve, and marketing to new segments also follows an S curve. This explains why certain approaches are incredibly effective but become less so as they approach saturation. Sales teams have jumped from door-to-door visits to phone calls (telemarketing) to email. In every instance, these approaches have eventually become less effective, until diminishing ROI drove adoption of new methods, like today, when conversational interfaces and social media are the preferred methods of lead generation.

This is why marketing, no matter how automated it becomes, will always invite innovation as old tactics lose their power.

The Speed of Information

The accelerating speed of information is the defining event of our current moment, whether you consider this to be a new industrial era or a continuation of the last.

The rate at which information is disseminated has accelerated the S-curve of business, as well as the demand cycle. It becomes a cyclical process: an accelerated demand cycle puts pressure on innovation, while accelerated innovation drives greater demand.

The final result is a shorter S-curve with a steeper slope, which favors more agile companies and processes. At the same time, a strong foundation of support and ample resources (inputs) are needed to climb the slope.

Riding the S-Curve

Half a century ago, a company could ride a single S-curve to prosperity, and enjoy a long and fruitful business life. Now, a company that wants longevity must diversify its innovation portfolio, continually investing in and nurturing new ideas while strategically maximizing the lifespan of ongoing innovations.

Other companies may eschew longevity entirely, determining instead to structure their business model to get in and get out quick. Pop-up shops, JIT manufacturing, coworking spaces and mobile tech all serve our experimental and innovative era by allowing innovators to quickly test and improvise, while developing new models and initiatives that can move us forward to a smarter, more efficient and, ultimately, more sustainable future.