Early in 2015, a pair of earnest colleagues pulled me aside to offer some career advice. They warned that innovation had jumped the shark. It was a done-with management trend, an overworked idea sliding down the wrong side of the hype curve, and I would do well to direct my passions elsewhere.

Looking back, it is clear to me they were more than a little bit wrong.

There is a good case to be made that in 2015, innovation claimed a level of business relevance that is more urgent and important than ever before. Innovation may have finally earned its long pants, moving beyond a seemingly perpetual state of adolescence, to become an enterprise necessity that legitimately deserves front and center executive concern.

The shifts in thinking and approach may not have been obvious in the noise of the daily news feed. So, in an attempt to defend my undiminished passion for enterprise invention, here are my four hidden innovation trends.

1. The End of Innocence

First hidden trend: Catastrophic disruption is finally taken seriously

Early in the year, in our meetings with business leadership teams, one of the most common questions was still, “What is innovation?”. It was a roundabout way of asking how quickly they could check the innovation box on their executive to-do list. “Would a big backlog of new product features qualify?” “How about an innovation lab”?

Unless you were in one of the ‘unlucky’ industries to be dismantled by some new technological invention, it was still acceptable to treat innovation as ‘nice to have’.

It was still possible to see the radical disruptions in other markets, as a product of technical revolutions that were unique to that unlucky business area. Newspapers were undone by the web. The music business was turned upside down by digital recording and distribution. These were cautionary tales, but isolated cases.

Then came Uber.

2015 saw Uber usurp Amazon’s role as innovation’s great boogie man. Here was a competitor that emerged out of nowhere, in an improbable business sector to devastate the incumbents. Uber built and deployed an entirely new business ecosystem, city after city. In less than a year, the value of New York City taxi medallions, a convenient measure of the capital value of a taxicab, plunged by 50%, from $1.4 million to $700,000.

What’s different? There is nothing magical. Uber doesn’t ride a wave of emergent technology. They created their disruptive, double-sided, market-leveraging, widely available mobile technology, but combined this with new ownership, labor models and vigorous regulatory advocacy.

Entrenched advantages of scale, capital, and business network are supposed to defend against this sort of thing. Yet, disruption was increasingly a threat to everyone. In 2015, AirBnB reached the same market valuation as Marriott, and Apple and Google were joining Elon Musk in plans to build cars, traditionally one of the world’s most capital-intensive industries.

Midway through the year, we sat with a major financial firm’s head of technology. He wasn’t debating the definition of innovation. Instead, he shook his head in amazement at his newly emerging competitors, saying, “We have a huge market position. We made this business. We had no idea how quickly someone could move to challenge that.”

Revolutionary business ecosystems are disruptive in a way that straight product-on-product competition can’t be. They don’t simply provide competitive advantage. They change the game, leaving incumbents irrelevant or deeply disadvantaged.

2015 seems to be the year where the reality of this threat was finally felt in the gut.

2. IoT: The Market Disruptor’s Toolkit

Second hidden trend: IoT becomes a tool of disruption

Using technology to fight harder over the same scraps of opportunity is not disruptive. It’s just hard-nosed business, a cage fight where customers are offered the same kind of value, just in different forms. In contrast, disruptive strategies change the rules. Disruptors escape from the box that has traditionally constrained business opportunity in their sector.

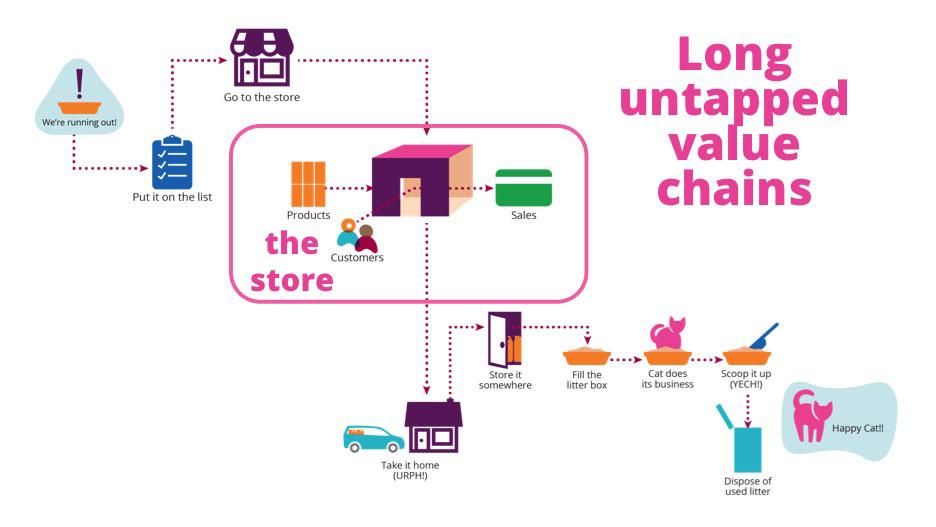

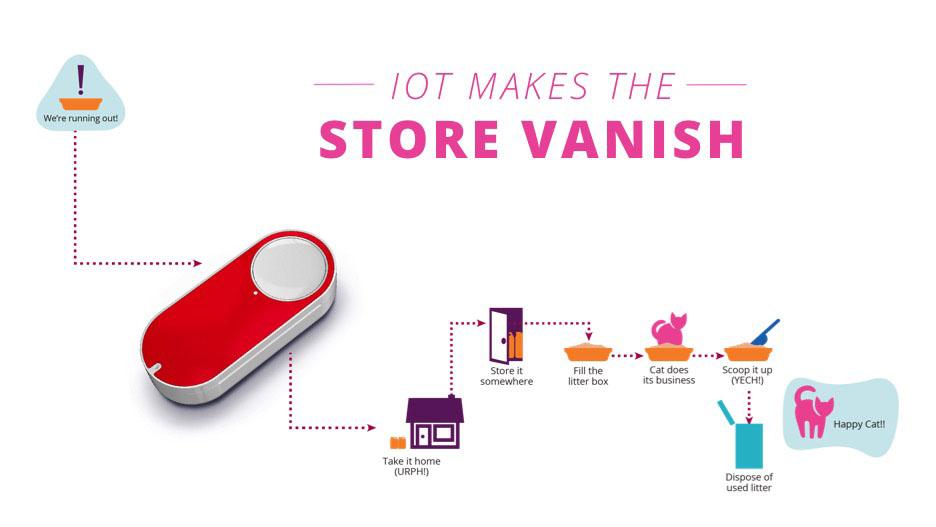

In 2015, the Internet of Things (IoT) demonstrated a unique power to enable this kind of disruption. Amazon released the Dash, a button that makes stores disappear. It’s an IoT device placed in the home, next to the place where products are kept and consumed. Customers simply smack the button when they run low.

This seems simple, but by following the customer home and delivering value at the moment of need, IoT severed the value chain, making the traditional store all but irrelevant. Competitors lose the opportunity for price or brand comparison, and those well-honed buying experiences and cutting-edge point of sale systems never enter the picture.

Like many new technologies, early in its adoption, IoT was often just a feature. It appeared as a bright and shiny enhancement to otherwise mundane products, like home thermostats. In 2015, IoT began to demonstrate how its impact could be more dramatic. Whether or not the Dash button is a long term success, it illustrates the power of the IoT to disrupt the fabric of existing business ecosystems.

When Tesla downloaded the programming necessary to create a self-driving vehicle into cars that were already in buyers hands, they demonstrated a shift in thinking. For years, cars have included substantial computational capacity, as much as a 100 million lines of code by some counts, but this technology was largely used to optimize the performance of cars against car owner’s traditional expectations. Now as a connected computing platform, new features, including radical extensions of value, can flow into the vehicle throughout its life. The car as an IoT device is one of the shifts in equilibrium that enables disruptive automotive ambitions from both Apple and Google.

At the end of 2015, IoT is poised to become part of a growing network of tools with mutual synergies. Even more disruptive strategies built around personal engagement will be possible, when the reach and immediacy of IOT is supported by sophisticated Big Data insights and with the ability to draw on a portfolio of distributed services from the Cloud.

3. Baby Bunnies Need to Grow Up

Third hidden trend: Scaling innovation is hard (and we’re bad at it).

The Humanitarian Sector is a field with a big mission and far too little funding for the level of need. To their credit, they have actively embraced Lean Startup models for innovation, creating challenge grant programs and supporting innovation labs that are intentionally user centric.

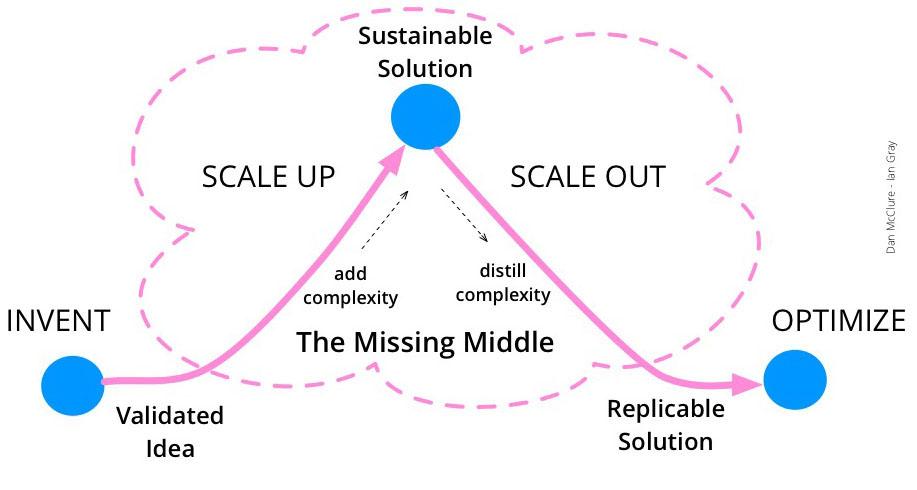

On paper this seems like an innovation win, but 2015 saw a growing recognition that while the sector had become very good at developing pilot programs, breeding them almost like baby bunnies, the number of good ideas going to scale was disappointingly small. Good ideas got stuck. It seemed that developing sustainable solutions at scale was not simply about making pilots bigger or replicating them in multiple contexts.

Commercial innovation teams increasingly found themselves answering similar questions. Innovation labs and other islands of creativity were being scrutinized. “Which ideas had actually gone to scale? What was the business impact?”

Lean Startup methodologies have proven themselves invaluable for early stage evaluation of design and product market fit, but when the idea must be adapted to a messy real world environment, innovators face a persistent gap. —We’ve called the part of the innovation lifecycle between early stage innovation and the mature ability to replicate a sustainable solution, the ‘messy middle’.

It’s increasingly clear that scaling can’t be done with the same tools and methodologies used for initial product discovery. Pilots are about speed, learning and creativity. Investments are (relatively) small. In contrast, building complex sustainable solutions is messy work complicated by dependencies, conflicting priorities, uncertainties, and change.

The hard lesson of 2015: getting a baby bunny to grow up is hard and almost everyone is bad at it. There is a job ahead, learning to deal with scaling challenges like evolving large legacy systems, working across business silos, and engaging with the soft messy challenges of cultural, business and regulatory change.

4. The Entire Enterprise Must Dance

Fourth hidden trend: A rush to create a responsive the enterprise

Many mature businesses are masters at making incremental improvements to existing offerings. A growing number have even invested in innovation labs that allow them to do experiments inside safely segregated pockets of creativity. However, it is an understatement to say that most organizations are ill prepared for a world where disruptive competitors emerge out of nowhere. With few exceptions, these enterprise cannot dance.

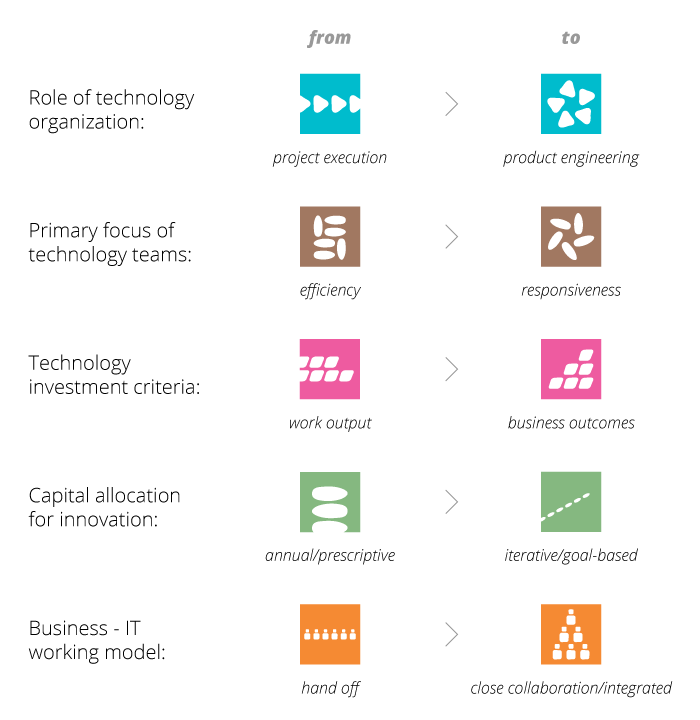

Given the competitive turmoil on the horizon, it is not surprising that 2015 saw a sudden growth in interest for new Lean Enterprise models. Executive leaders dramatically increased their appetite for radical change, acting on a realization that businesses need a strategic capacity to pursue new opportunities with speed and agility.

(Image from Aneesh Lele / Anupam Kundu – Winning Companies Master Strategic Tech)

Lean Enterprise models are a big shift. At the root of this transformation, is a move from a command and control management model, where plans are made annually by senior leaders and executed within budget by assigned teams. In its place is a responsive model based on learning loops, where actors at all levels of the organization quickly respond to new insights and feedback.

Learning loops are designed for business environments where the biggest risk is failing to move quickly and responding creatively to new insights. Choices are made in close proximity to the moment of learning, promoting both nimble action and the chance to gain new insights.

This is a deeply transformative change for most traditionally managed organizations. It places new demands on every level of the enterprise, offering more freedom and demanding more responsibility. It’s hard, yet 2015 found an unprecedented leadership appetite for this type of transformative change.

2016–A Year for Bigger Innovation

The need for Big Innovation is driven by opportunities (and threats) rooted in the market’s capacity to create disruptive new business ecosystems. My friends were wrong. Innovation did not become irrelevant in 2015. Instead, creativity at the enterprise level became a more urgent need than ever before.

Now Innovators are being asked to do far more difficult things, for far higher stakes. That should make 2016 a pretty interesting year.

An earlier version of this article was first published on ThoughtWorks Insights.